Australia’s space achievements stretch back to the 1960s, when it became the seventh nation to launch a satellite into orbit.

Named the Weapons Research Establishment Satellite (WRESAT), the 45kg spacecraft was designed and built by Australians and took off from the Woomera Test Range in South Australia on November 29 1967.

After 642 orbits of the earth, the satellite reentered the atmosphere 42 days later when it landed in the Atlantic Ocean.

It was an exciting time for space research, with Australia a member of the European Launcher Development Organisation and Woomera used as a testing ground.

Fast forward to the present day and the space industry has grown tremendously from those pioneering days punctuated by that one small step for [a] man and one giant leap for mankind on July 20 1969, when Neil Armstrong walked on the Moon.

However, the era of big satellites and expensive space programs appears to have given way to what some are calling Space 2.0, as University of New South Wales director of the Australian Centre for Space Engineering Research (ACSER) Professor Andrew Dempster explains.

“Space 2.0 is about relatively low-cost access to space, so building quite small satellites and making it cheaper to launch,” Prof Dempster told Australian Aviation in an interview.

“Quite a lot of things are changing and Australia is actually well placed to avoid some of the traditional problems or the slow-moving nature of the old method, the old Space 1.0 if you like.”

In such an environment, the Australian government has committed to establishing a national space agency.

A GREEN LIGHT FOR AN AUSTRALIAN SPACE AGENCY

Acting Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science Michaelia Cash made the announcement at the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide in late September. Currently, Australia is one of the few developed nations without a national space agency, a source of some lament for many years among those who work in the sector.

“It will provide the vehicle for Australia to have a long-term strategic plan for space – a plan that supports the innovative application of space technologies and grows our domestic space industry, including through defence space procurement,” Senator Cash said.

While Canberra has committed to set up a national space agency, it has offered few details on how the agency would be structured.

Instead, the matter was being examined by the federal government’s Expert Reference Group chaired by former CSIRO chief Dr Megan Clark, with 200 submissions received in response to an issues paper released earlier in 2017.

The reference group was expected to develop a charter and advise on the possible structure and scope for Australia’s national space agency by the end of March 2018.

“This is not just about an agency for an agency’s sake: that is why this review process is so important. We now need to put in the hard work to determine what form of agency and what mandate is best suited to support our growing space industry,” Senator Cash said.

“I have heard people ask ‘why even have a review?’. Well, the space industry of today is not the same as it was a decade ago, and likely not the same as it will be a decade from now.

“It is crucial that we take the time now to understand that landscape and create the structures and policies – and the agency – that are right for the industry of today and tomorrow, not the industry of yesterday.

“And so when people ask will we have a NASA? No. We will have an Australian space agency. Right for our nation, and right for our industry.”

Space Industry Association of Australia (SIAA) chair Michael Davis said it was “very pleasing” the government had finally understood the importance of a national space agency.

“I’m optimistic that we will be able to in some ways leapfrog over our international competitors and design a national space program that really takes advantage of latest technologies and the future plans for activities in space internationally,” Davis told Australian Aviation.

Davis said the national space agency should have three main functions – industry development, representing the country in international fora and community outreach.

Taking each in turn, industry development would typically involve programs to assist researchers to progress their ideas, their technologies and their systems into products and services that can be commercialised. This would help create jobs and generate economic activity.

On the international front, the Australian Government already did a lot of work in regulating aspects of space activity that require regulation under international law, such as the need for a licence to launch orbital satellites from Australia or the launching of Australian-made satellites overseas.

Davis noted local legislation covering these matters was currently being reviewed and he was hopeful a new set of rules would make it easier for smaller players to get into this space, including universities and start-ups developing smaller satellites that have become the fastest growing sector of the industry.

And finally, Davis said inspiring the next generation to look to a career in the space sector would benefit the whole of society.

“We think outreach to fire the imagination of young people to encourage them to study science technology, engineering and maths in the hope of one day joining the international space industry is equally important,” Davis said.

“We saw this at the International Astronautical Congress where young people, especially kids in primary school, were absolutely fascinated by space and loved learning about it, loved hearing about and loved hearing stories from astronauts.

“We think in that way a space agency has an important role in encouraging young people to become scientists and engineers, as well as the other disciplines involved in space, giving them opportunity eventually to pursue interesting careers and make important contributions to the economy, whether or not they end up working in the space sector.”

UNSW’s Prof Dempster was hopeful the committee will come up with recommendations on the national space agency that would “deliver something good”.

“What we do not want is just a room full of bureaucrats. That’s the wrong solution here,” Prof Dempster said.

“What we really want is an active agency, which is proactively coming up with ideas – Australian solutions to Australian problems – and we want those people working with international agencies, we want them facilitating growth in the sector.

“We really want to make things happen here. We want technical people, not bureaucrats, working in that office.

“I think the agency they are talking about will be very industry-focused so it will be aimed at developing new startups, facilitating the way space business is done in Australia and hopefully that will be far more productive and much smoother and easier.”

SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL

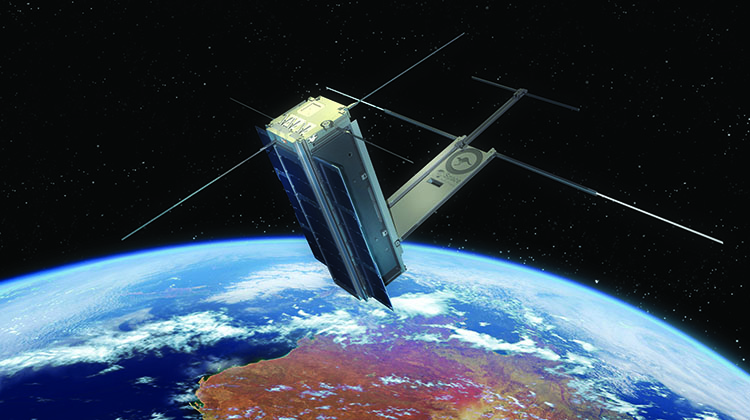

Australia has been prominent in the new fields of space, particularly in terms of these new smaller satellites known as cubesats that can be the size of a loaf of bread and weigh as little as two kilograms.

Indeed, three Australian cubesats were launched in April 2017 – the UNSW ACSER-built UNSW-EC0, INSPIRE-2 (a joint project between the UNSW, University of Sydney and Australian National University) and the University of Adelaide’s SuSAT.

UNSW’s ACSER also built space GPS hardware and software for Project Biarri, a cubesat mission by Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Group that is part of the Five Eyes defence agreement with Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, UNSW said.

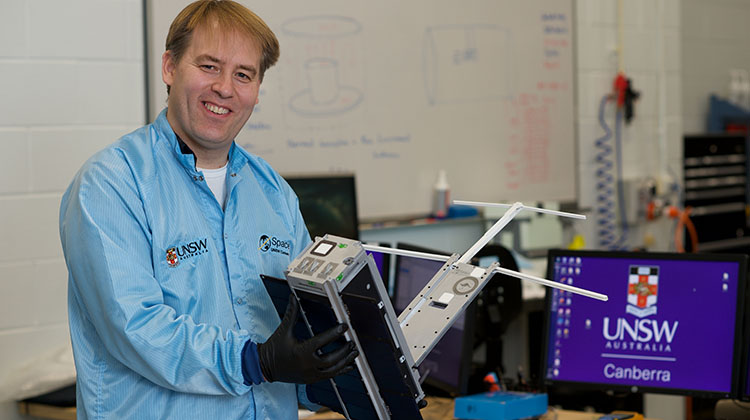

Further, UNSW Canberra said in late September it had secured a $10 million contract to build three of these mini satellites for the Australian Government to boost its surveillance capabilities.

The project was part of a three-year space research and development program involving UNSW Canberra, the Australian Defence Force Academy and the Royal Australian Air Force.

The first satellite will launch in early 2018, with a second launch planned for the following year.

UNSW Canberra space director Professor Russell Boyce said the cubesats were earmarked for the Australian Defence Force to use on maritime surveillance.

“These spacecraft are able to gather remote sensing information with radios and cameras, and are the sort of innovative space capability that can help meet many ground-based needs in ways that make sense for Australia,” Prof Boyce said in a statement.

“Because they have re-programmable software defined radios on board, we can change their purpose on the fly during the mission, which greatly improves the spacecraft’s functional capabilities for multiple use by Defence.”

Federal Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne said the three miniature satellites would provide an “opportunity to demonstrate innovative communications and remote-sensing payloads, and test spaceflight modelling techniques”.

Further, it would also “help achieve a secure, resilient Australia by supporting the protection of our space systems from debris and anti-satellite weapons”.

“Partnerships such as this are an integral element of our Defence Force,” Pyne said in a statement.

“The expansion of space research and development into a regional academic institution provides Defence with an opportunity to build, sustain and create momentum to develop our space professionals.”

Prof Dempster said the small satellite market, which includes cubesats and nanosatellites, was growing at about 20 per cent a year.

“Of course what it means is, it is possible for small startups, for universities, even schools to put satellites into space. This is a bit of a game-changer,” Prof Dempster said.

“People have expected space to be big and expensive, it doesn’t necessarily have to be.”

Further, he said Australian startups were rushing to get involved in space.

“The rate at which startups are forming in Australia is really rapid and Australia is overrepresented by these startups so things are actually looking quite good for us,” Prof Dempster said.

“It really is an opportunity for Australia to get stuck in and join a global big success story.”

Figures compiled by the SIAA showed there were about 400 organisations, including government bodies and universities, with space expertise in Australia.

An SIAA White Paper published in March found the Australian space sector represented about 0.8 per cent of the global space economy, generating annual revenues of $3-4 billion and employing between 9,500-11,500 people.

The White Paper estimated that having an Australian space agency leading a cohesive national space strategy could double the size of the industry within five years.

“That would then make the size of our sector more equivalent to our share of international GDP,” Davis said.

The space sector in Australia involved both building things designed to go to space, as well as taking advantage of the data that satellites gather from space.

“The upstream sector is developing things to fly in space, developing our own national assets that assist with important activities such as environmental monitoring, weather forecasting, positioning, navigation and timing, and of course telecommunications which is a very big international industry,” Davis explained.

“There is also the downstream sector, making intelligent use of the data that we get from satellites and assisting other industries.

“We now know that space data is very important for industries such as banking, precision agriculture, mining and air navigation. All of these industries now rely on satellite data and there is an opportunity for Australian companies to be part of that global supply chain.”

Other projects that were announced at the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide included a memorandum of understanding between the University of Sydney and Germany’s national space agency the German Aerospace Center (DLR) to work on collaborative research, teaching and other activities that could include building an Australian-first multi-spectral satellite.

“We would like for DLR to help us with the design, building, integration, testing, launch preparation and operations of a small 0.5 cubic metre volume, 150kg Earth observation satellite, which we are calling the ‘Multi Spectral Satellite for Australia and Deutschland’ – or MISAD for short,” University of Sydney executive director of space engineering Warwick Holmes said in a statement.

“If the project gets the go ahead, we believe it will also be the most advanced and sophisticated satellite built in Australia to date.

“MISAD will be the Australian version of DLR’s well-known BIROS [Berlin InfraRed Optical System] satellite, which has been deployed on missions to detect and monitor high-temperature events, such as forest fires.”

MISAD would carry specialised multi-spectral cameras to capture images of the Australian landscape to help farmers, environmentalists, government departments and geographical information systems for the benefit of all Australians. The cameras would also be optimised to detect water quality of lakes, rivers and dams.

Davis noted Australia had a long history in space exploration and development, which would only be enhanced with a national space agency.

“We are not starting from a zero base, we are starting from 60 years of activity in space in this country,” he said.

“It’s just that we have organised ourselves differently in this country over the last 60 years from most countries, for various historical reasons.”

G’DAY FROM MARS?

There have been just two Australian-born astronauts who have gone into space – Paul Scully-Power and Andy Thomas. However, the pair had to become US citizens in order to do so.

Having a national space agency would remove the need to relinquish Australian citizenship in order to take off for the Moon, Mars or anywhere else.

“Until now, anyone wanting to become an astronaut had the odds stacked against them,” Prof Dempster said.

“They had to become citizens of a another country, like the US, and then work hard to get into a space agency like NASA. That won’t be the case any more: in fact, the first home-grown astronaut may only be years away.

“When your country has an agency, your citizens can be astronauts. Australian kids can now aspire to be astronauts without having to change their nationality. It’s quite an important point.”

This feature story first appeared in the November 2017 issue of Australian Aviation.