This story first appeared in the March 2019 edition of Australian Aviation.

It seems ironic that Abu Dhabi-based Etihad Airways in January announced a major cabin crew recruitment drive over the next 12 months in 19 different cities across Australia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa to add to the 4,800 flight attendants it already has.

The reason? To “support its operational growth including the arrival of new, next generation fleet this year”.

Why ironic? Just a month earlier, in an internal memo, the airline told its 2,065 pilots that 50 of them would be out of a job by the end of January and that about 160 were surplus to requirements.

On the surface, none of that appears to make sense. Yet it does reflect the fact that industry concerns about the potential for a serious pilot shortage in coming years are by no means universal. While Etihad trims its pilot numbers, elsewhere, particularly in the Asia Pacific region, airlines are taking steps to bolster their pilot training channels and retain the experienced cockpit crew they already have. The launch of two new Qantas pilot training academies, the first at Wellcamp Airport in Toowoomba (the location of the second has yet to be announced) has been well publicised.

Singapore Airlines has the joint venture (JV) Airbus Asia Training Centre (ATC) and in August last year launched another JV with CAE – Singapore CAE Flight Training (SCFT) – to expand pilot training.

SIA chief executive Goh Choon Phong says the Airbus venture has already been a tremendous success. “We have over 40 airlines from all over the world training with us and, as we speak, we are looking at how we can actually look at perhaps even extending it further from what we have planned.”

Elsewhere, major airlines have suffered pilot losses through poaching, particularly by the rapidly expanding Chinese carriers. Korean Air, in particular, has lost cockpit crew to China. And Thai Airways International in December increased pilot allowances in a bid to stop poaching by competitors.

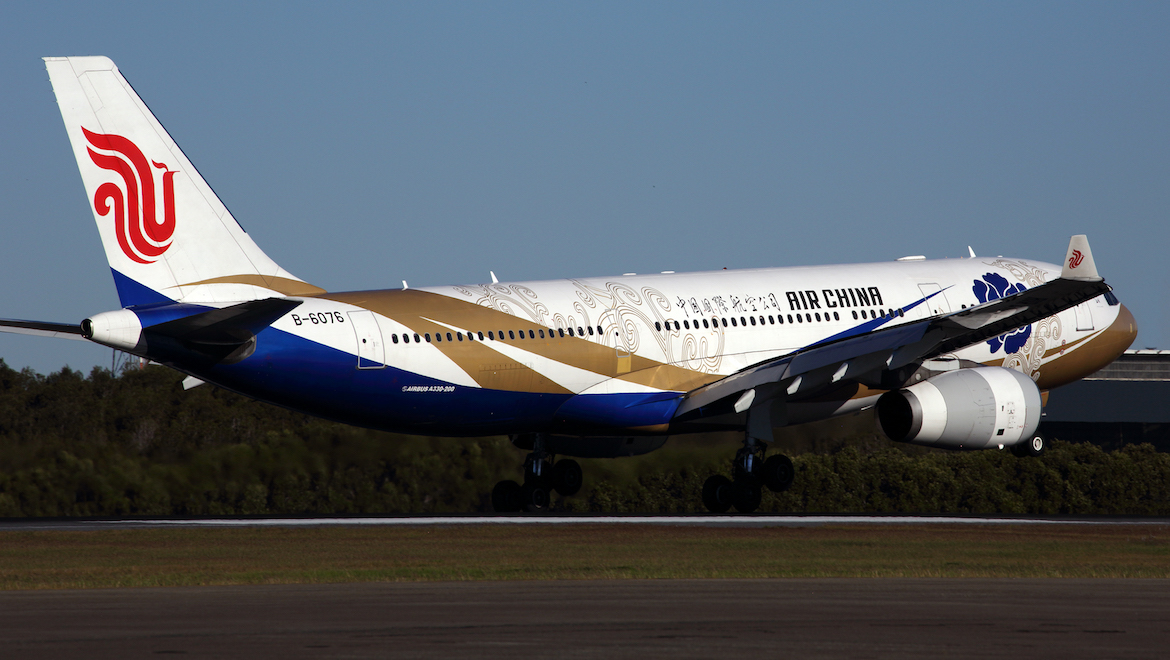

Consider the planned growth of Chinese airlines and their need for more pilots. Guanghzhou-based China Southern Airlines saw its fleet pass the 800 mark late last year. It says the fleet will grow to 1,000 by 2022 and 2,000 by 2035. Beijing-based Air China and Shanghai-based China Eastern Airlines are not far behind.

China isn’t the only problem. The rapid growth in Asia of low-cost carriers (LCCs) has seen the budgeteers offer better wages and conditions to lure pilots away from their mainline competitors. That situation threatens to worsen.

According to placed orders at Boeing and Airbus, eight Asian LCCs have a staggering 2,047 new jets on order. They are from Indonesia’s Lion Air (444), India’s IndiGo (399), SpiceJet (190) and GoAir (114), Malaysia’s AirAsia (375) and AirAsia X (110), Vietnam’s VietJet Air ((316) and Jetstar (99). These numbers are impressive and the future pilot demand picture looks even bleaker globally.

According to Boeing, about 42,730 jets will be delivered worth around US$6.3 trillion through to 2037. Airbus thinks 37,400 jets worth $5.8 trillion. In its latest forecast Boeing predicts a need for 635,000 pilots, 622,000 commercial technicians, and 858,000 cabin crew members for a total of 2,115,000, over the next 20 years.

Will those forecasts prove to be accurate? Some in the industry believe that new technology, a digital revolution if you will, is set to save the day and solve the problem. At last year’s Farnborough Air Show it became clear that both Boeing and Airbus are seriously looking at ways to actually reduce the number of pilots in the cockpit, particularly on long-haul flights. Ramping up pilot training is only part of the solution. Airbus and aerospace firm Thales think the number of pilots on long-haul flights, typically three or four, could be reduced to two by around 2023 thanks to new technology to reduce pilot workload.

“That’s not an absurd date. Reducing crew on long-range looks to be the most accessible step because there is another pilot onboard,” Jean-Brice Dumont, Airbus head of engineering told reporters. Boeing isn’t making any public comment but is also understood to be examining the possibility of having reduced manning in the cockpit of a proposed midsized jet that could be in service by 2025, a program yet to be officially launched.

Reduction of crew in the cockpit is, after all, nothing new. In the 1980s cockpit crew numbers were cut from three to two as new jets arrived, eliminating the need for a flight engineer. Research by both manufacturers is understood to involve such things as embedding artificial intelligence into cockpits, connectivity that allows for decision-making on the ground, and replacing the vast array of knobs and switches with more digital interfaces familiar to today’s young generation. That could also help shorten the amount of time it takes to train pilots, helping to ease the shortage.

Could we see a fully autonomous commercial jet along the lines of a driverless car? Thales sees that as a possibility but suggests it may not become a reality until around 2040. As for having one pilot in the cockpit, financial services group UBS believes that could save airlines some $15 billion annually. On the other hand, a poll conducted by UBS found only 13 per cent of respondents would board a jet with a single pilot. Critics also point out there are good safety reasons for having more than two pilots in the cockpit on long-haul flights and at least two on shorter journeys, with the costs outweighed by the benefits.

There would also need to be adjustments in training systems because having a second pilot in the cockpit, a First Officer, is an essential part of the path towards becoming a Captain.

New technology and reductions in cockpit crew are probably inevitable in the long term but another hurdle that will have to be overcome is the regulatory one. Convincing regulators such changes are safe will be a tough sell. Besides, Airbus’s Dumont says the single pilot operation is not an absolute must. “But it may be made a necessity by the fact there is a disconnect between the number of aircraft and the number of pilots.”

One senior industry figure who has always believed the pilot shortage issue will be resolved by airlines is Andrew Herdman, director general of the Association of Asia Pacific Airlines (AAPA). He has said there is a bidding war going on. “When I hear the talk about pilot shortages I think it reflects the pressure that airlines feel where there’s movement within the pilot community; upward pressure on salaries. And you’re seeing pilots moving around internationally which, of course, is the big feature, particularly in our part of the world where expatriate pilots are 10 per cent of the workforce.

“So airlines feel the pressure on pilot salaries, particularly in lower cost countries.”

This happened in the past when the fast-expanding Gulf carriers poached pilots from competitors across the world, particularly in Asia, with big salary offers. That has eased because of a slowdown in the Gulf, only to be replaced by China.

“The Chinese market is enormous now, with half a billion passengers. It’s been growing at double digit rates for the last two decades and I think roughly 10 per cent of the pilots operating in China are now expatriates.

“China is recruiting a lot of pilots and some of that is drawn from the major Asian carriers, although they are advertising worldwide,” said Herdman.

If an airline is suffering a pilot shortfall it may be not so much the result of a shortage of available pilots but more a reflection of where the carrier is in terms of the international competitiveness of its salary packages.

“If you are out of line, you’re going to find you will be losing pilots, and losing trained pilots is a much bigger headache that thinking about how many trained pilots you need to bring in to the system from a training point of view. If you lose senior first officers and captains these can’t be easily replaced, particularly as a lot of airlines have rules against employing direct entry captains,” Herdman explained.

Meanwhile, the expansion of present-day pilot training offerings is continuing apace as providers develop their facilities to meet the rising demand. Airbus and Boeing, as well as major training organisations such as CAE, AVIA Solutions Group, Alpha Aviation, FlightSafety International, L3 Commercial Training Solutions (L3 CTS) and others are all adding simulators and increasing their training capacity.

China, where pilot training is problematic because of severe restrictions caused by military control of much of the nation’s skies, has become a real target for training suppliers. Currently, about 1,500 pilots who work for Chinese carriers are being trained abroad each year. Avia Solutions Group, a Lithuania-based aviation services company, has announced plans to establish a pilot training centre in China with a planned opening in 2020. The company said it will provide training services for existing pilots and for smaller airlines that do not have simulators.

Avia is looking for Chinese partners and considering suitable sites for the centre. Gediminas Ziemelis, chairman of the board of Avia Solutions Group, said that by 2022 the facility will be training 1,000 pilots a year with three simulators, mostly for Airbus A320 and Boeing B737 MAX aircraft. Later, it will increase this to 2,000 pilots annually with six simulators. Whether it will be able to overcome Chinese regulatory issues is another question.

Boeing is also extremely active on the pilot training front in China. “That is certainly one of the bigger challenges here in China as they continue these double-digit growth rates in traffic,” explained John Bruns, Beijing-based President of Boeing China.

“We have been working on pilot training in China for more than a couple of decades now and we have recently been working on something called a Pilot Development Program to help. This is generally working at the moment with some of the smaller carriers in China, to help them with sourcing and bringing new pilots into the system to work for them.”

That program was expanded last year, adding China’s Okay Airlines, where Boeing will oversee screening, selection and training of 100 pilot cadets over the next five years. Cadet training for YTO Airlines and Kunming Airlines was already underway.

Through the Pilot Development Program, Boeing works with a network of flight schools around the globe to provide airlines with comprehensive commercial training including screening cadets, managing student performance and correction, and developing commercial pilot training courses and materials. The comprehensive program includes ab-initio – pilot training from zero-flight-hour experience through advanced flight training – and is designed to develop cadets into B737 type-rated first officers.

“That’s going to be a big emphasis for us going forward in the future,” Bruns explained. “Of course, it’s not only pilots, it’s mechanics and engineers and other specialists. We have a training centre in Shanghai, a wholly-owned facility with probably half a dozen simulators. We do a lot of our entitlement training there which comes along with aircraft purchase deals, so it’s transitioning pilots into a new model like the B787.”

Airbus’ Hua-Ou Aviation Training Centre in Beijing provides training to most Chinese airlines, as well as operators from Asia, Europe and other regions of the world. Since being established in 1997 it has trained more than 24,000 professionals from more than 30 airlines worldwide, including pilots, cabin crew, flight operations personnel, and maintenance and structure technicians. It is a joint-venture between Airbus and China Aviation Supplies Import & Export Corporation (CASC).

Airbus also last July launched an ab-initio Pilot Cadet Training Program to help meet global demand for pilots over the next 20 years. The programme is being launched in partnership with Escuela de Aviacion Mexico (EAM), located near the Airbus Mexico Training Centre. After completing their initial training with EAM, cadets will qualify at the Airbus centre to become Airbus A320 pilots.

India is another problem area. Air traffic is growing in excess of 20 per cent monthly, and while no-one is making much money the country has an acute shortage of pilots. The Indian government has had to extend a deadline which required the country’s airlines to phase out foreign pilots by December 31 last year. They have now been given until December 31, 2020 to meet the requirement.

“Presently, scheduled Indian airlines have over 7,000 pilots for their combined fleet of over 600 planes. This year itself the shortage is of over 250 pilots. Given the order books of our airlines, 1,100 aircraft are supposed to join in the next seven to eight years that will require over 10,000 additional pilots,” said Kapil Kaul, chief executive and director of CAPA (Centre for Asia Pacific – South Asia).

According to a CAPA report, India will need 16,802 new pilots by March 2027. CAPA said aircraft are once again being grounded in India due to a shortage of pilots, as was the case 10 years ago.

In Australia too, there is training growth. Apart from Qantas, in January Melbourne’s RMIT University announced a new aviation training school partnership with Parafield, South Australia-based Hartwig Air in response to the growing worldwide pilot shortage.

As part of the partnership, an entry-level Associate Degree in Aviation is set to be delivered in part by Hartwig Air in South Australia on behalf of RMIT, meaning South Australian students will no longer need to immediately relocate to Victoria to gain in-demand aviation skills.

Hartwig Air chief executive Captain David Blake said about 5,000 pilots were trained every year in Australia, but there was still a gap of approximately 9,000. “We know the aviation industry needs qualified pilots and we are confident the Hartwig Air-RMIT partnership can help address some of this unprecedented demand,” he said.

With three campuses and two sites in Australia, two campuses in Vietnam and a research and industry collaboration centre in Barcelona, RMIT is a truly global university. The RMIT Flight Training School was established in 1994 and has trained more than 3,000 pilots from around the world, with many now holding senior roles with major airlines such as Qantas, Virgin Australia, Cathay Pacific, Oman Air and Air China.

What is clear is that whether or not forecasts and expectations of pilot shortages prove to be correct, the industry is not ignoring the issue.

Alexandre de Juniac, director-general of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), agreed shortages are starting to be a problem in some parts of the world and could become a problem to more airlines.

He said IATA is working with others at “dimensioning properly” the training system. “I am confident they (airlines) are taking appropriate measures,” he said.

This story first appeared in the March 2019 edition of Australian Aviation. To read more stories like this, become a member here.