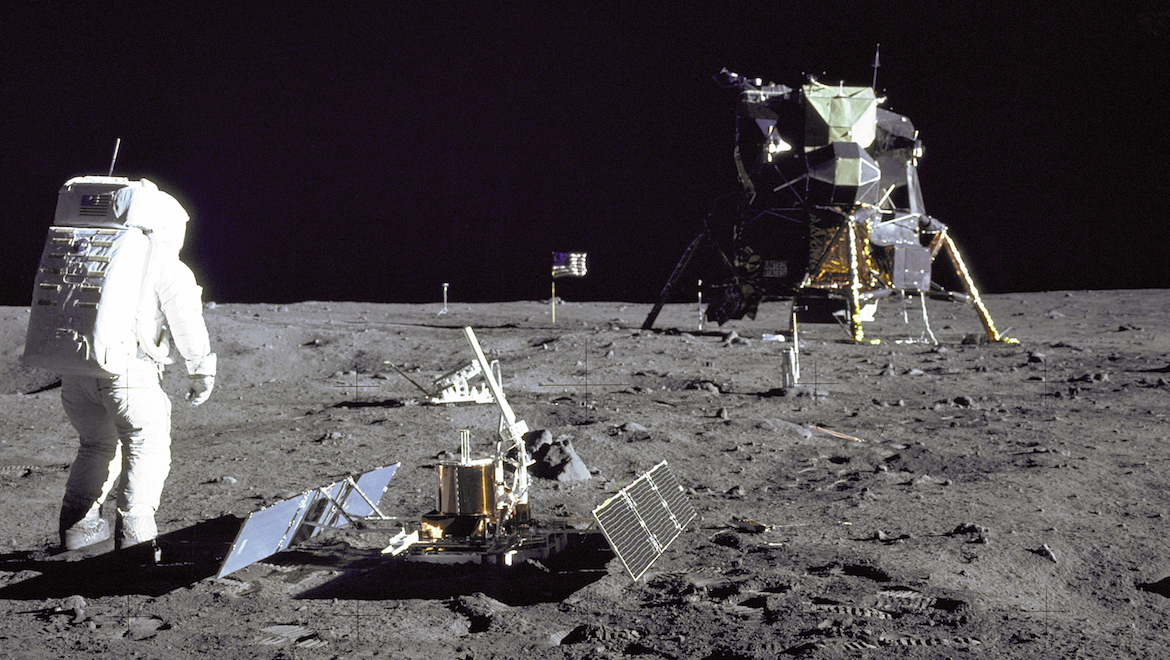

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20 1969, Denise McNabb writes about listening to that historic moment in a school classroom and the extraordinary efforts taken to ensure New Zealanders would be able to watch Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon.

“The Eagle has landed.”

“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

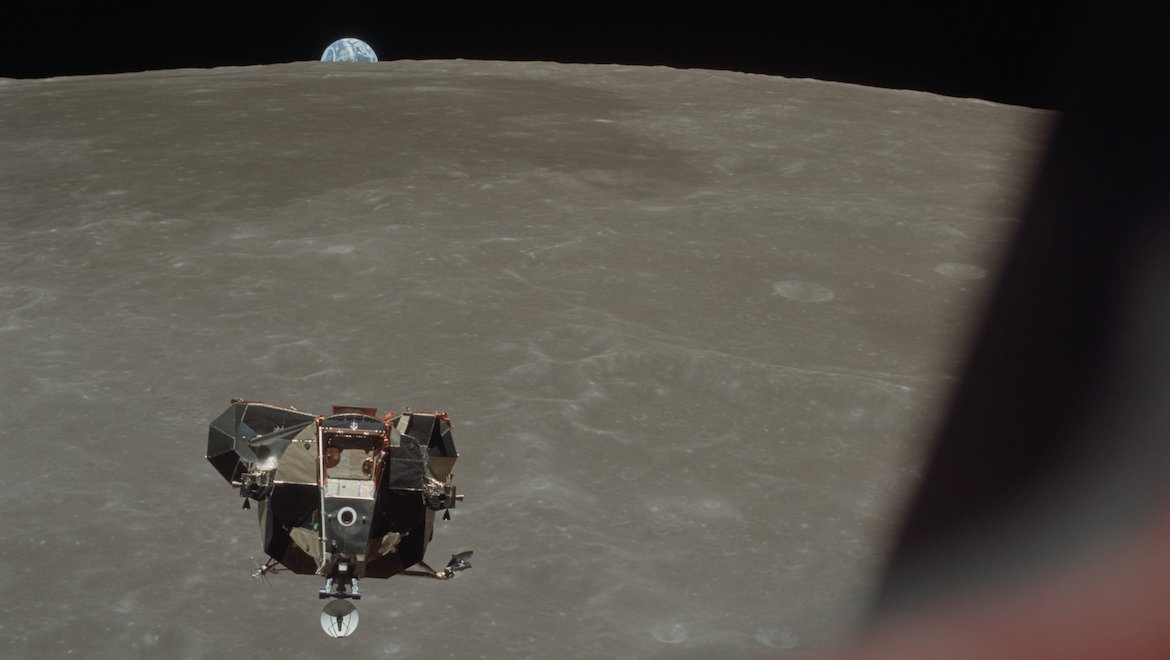

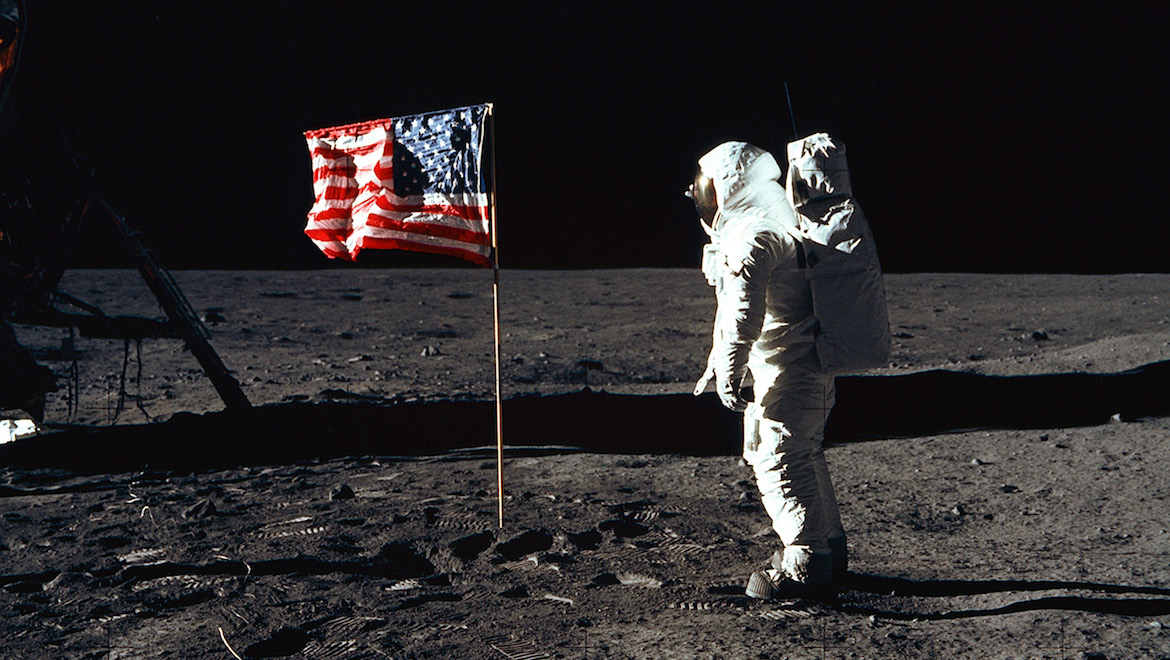

The words of astronaut Neil Armstrong, the first person to set foot on the moon and then walk with Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin 20 minutes later across the moon’s dusty surface on July 20, 1969, immortalised the Eagle lunar module landing.

Due to the different time zones it was 1256 on Monday, July 21 on Australia’s east coast and 1456 in New Zealand when Armstrong literally leapt into the history books at 2356 co-ordinated Universal Time (UTC).

Australians know well the pivotal role that the radio telescope and small dish at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s (CSIRO) giant dish and telescope at Parkes in central New South Wales and the Deep Space Communications Complex at Tidbindilla played in keeping contact with the command module and getting the first video footage from the lunar module out live to more than 600 million people watching television worldwide.

Timing was everything. The astronauts, high on adrenaline, skipped their nap, bringing their moonwalk forward. The moon dipped below the horizon at Goldstone, the prime ground station in California’s Mojave Desert for Houston’s Mission Control for the broadcast that initially appeared upside down because of confusion around inverting the scanner.

Then as the moon came over the horizon in Australia, Houston made the decision to switch to Australia, one of three places (Spain was the third) designated to relay signals.

The wind storm that whipped up at Parkes shuddering the giant 64 metre dish, tilted hard on its side towards the moon, back against its zenith axis right before Armstrong’s crucial step backwards down the ladder of the lunar module.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) telescope and dish at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, saved the day, relaying the first nine minutes of the historic step down on the moon’s surface before transmission reverted back to Parkes where the wind had luckily abated.

It would take over relaying the live grainy footage to the world via the International Exchange operated by the Overseas Telecommunications Commission in downtown Sydney.

Classroom memory

As a schoolgirl in New Zealand transfixed by the radio broadcast of the moon landing via a radio on the classroom intercom system, the moment is forever seared in the memory bank, even though my young mind wasn’t then cognisant of how lucky we were to be witnessing such a defining milestone of the 20th century.

It was nearing the end of the school day when our teacher tuned in to the American voices at Mission Control conversing with astronaut trio Commander Neil Armstrong, lunar module pilot Air Force Colonel Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and command module pilot Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Michael Collins.

Their voices were muffled, scratchy, crackly and interspersed with beeps and squeaks but those famous quotes were clearly audible.

Four days earlier the astronauts on the Apollo 11 moon mission had been launched into space from Cape Kennedy (named in honour of the late President John Kennedy but later returned to its original name of Cape Canaveral) in Florida on a Saturn V rocket.

School moon projects in the lead up to the mission meant we knew the names of the astronauts, about the command module (Columbia) – the only part that would return to earth – the service module containing the main propulsion system and supplies and the lunar module (nicknamed Eagle), the two-person craft Armstrong and Aldrin would climb out of on to a ladder to walk on the moon and plant an American flag, collect rock samples and explore.

That day, from the radio we listened to what seemed like hours of conversations. It was probably closer to half an hour before school was out. During the last 1,000ft we heard:

Eagle: (Aldrin) “Thirty feet, down two and a half. Picking up some dust . . . just moving to the right a little . . . contact light, OK engine stopped . . . defuel on the descent . . . engine auto over. Out . . . engine arm off . . .(inaudible) is in.”

Capcom: (mission control ground capsule communicator) “Roger we copy. You’re down Eagle.”

Eagle: (Armstrong) “Houston, [Sea of] Tranquility base here. The Eagle has landed.”

New Zealand mission

In 1969, there were no satellite earth stations in New Zealand, so live television coverage from the lunar module was not an option, unlike Australia and many other parts of the world where relays of the video footage were going out to televisions within seconds of the footage reaching earth.

Back then the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation (NZBC) got international news from Sydney where it arrived via satellite.

The national broadcaster had an arrangement with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) for videotapes to be packaged then flown on commercial air services to New Zealand for airing, usually the day after an event.

But the moon landing was no “next-day” event. As New Zealanders tuned in to their transistor radios up and down the country they were oblivious to another “moon mission” being hatched to deliver an evening surprise.

The 50th anniversary of the moon landing has brought it all back for Gavin Trethewey. In 1969, the 29-year-old Trethewey was an experienced pilot with the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), based in Ohakea, north of Wellington.

“We heard about our mission only a couple of days before the lunar landing,” Trethewey recalled in an interview with Australian Aviation this week.

The brief was for him and navigator Mike Hill to take a Canberra B1-12 bomber to Sydney Airport, retrieve a tape of the moon landing and get it back to Wellington in the fastest time possible so that viewers could get the first glimpse of the historic event on the news that night.

Trethewey said hiring an air force jet was the only way possible the NZBC could get the tape in time, as commercial airline services were on schedules that could not readily be changed. At the time, Air New Zealand was flying Lockheed L-188 Electras between Sydney and Wellington.

Not only did the national broadcaster hire the bomber jet, it also arranged advanced customs clearance at both Sydney, and Wellington airports, plus a speedy police escort with a Transport Ministry officer to the Wellington studio after delivery.

Trethewey said he and Hill set off from the Ohakea Air Force base on the morning of July 21 to arrive in time to watch the moon landing live in a small operations room at Sydney Airport while they waited for the videotape to arrive from the ABC’s Gore Hill studios, north of Sydney.

He said the bomber was parked near where they were waiting, out of the way of commercial aircraft. New Zealanders didn’t need passports to travel to Australia in those days, so it was one less formality to worry about.

“As soon as the tape arrived we threw it in the plane and took off,” Trethewey said.

It was a tight schedule. New Zealand’s time zone was two hours ahead of Australia. Leaving Sydney around 1630 New Zealand time, they landed at Wellington Airport at 1900, half an hour before it was due to go to air on the 1930 news.

Trethewey recalls a police car taking off from the airport with lights flashing. The 40-minute tape made it in time for a nationwide hook-up arranged in preceding days so that New Zealanders could see the moon walk hours instead of days after it happened.

After delivering the tape, Trethewey flew the jet back to Ohakea that same night to find that he had inadvertently set an unofficial record for a trans-Tasman flight on the return journey of two hours and 25 minutes.

The former training pilot, whose love of flying started at an early age, had a career both as an air force pilot and trainer and civilian pilot for Air New Zealand. His passion for flying these days is in the form of warbirds and he is an active member of the New Zealand Warbirds Association Auckland branch.

Some interesting facts about the moon mission, then and now

- The Apollo moon mission took off from Cape Kennedy Florida 724 milliseconds late. That’s a shade over half a second.

- The rocket started off at 17,500 miles an hour before boosting to 25,000 miles an hour.

- Armstrong had just 15 seconds of fuel left when he over-rode an on-board computer and manually flew the lunar module to a safe landing spot on the crater-riddled moon surface. “It’s grey and very white, chalk grey . . . and considerably darker,” were Armstrong’s first words about the texture of the earth in the Sea of Tranquility where the lunar module landed.

- To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, NASA has restored Mission Control in Houston to how it looked on the day of the event in 1969, right down to the carpet and wallpaper.

VIDEO: A look at Mission Control in Houston from NASA’s YouTube channel.

- Along with the US flag, the astronauts carried miniature flags of 135 foreign nations, including those from Australia and New Zealand, and the Soviet Union. In 1970, United States President Richard Nixon gifted to each of the countries represented by the flags small granules of moon rock sealed in a plastic capsule that were embedded into a plaque mounted with the miniature flags. Many are now lost or have been “taken” into private ownership. The New Zealand plaque is on display at the National Te Papa Museum in Wellington. The Australian plaque has been in the care of the Australian National Archives and is presently on display at the foyer of Questacon (the National Science and Technology Centre) in Parkes during celebrations of the 50th anniversary landing.

They're from Apollo missions 11 & 17 and were presented to 'the people of New Zealand' by President Richard Nixon. pic.twitter.com/juw6xXjRsH

— Te Papa (@Te_Papa) July 9, 2019

- To celebrate the 50th anniversary, Geoscience Australia, the National Museum of Australia, Questacon, CSIRO and the Australian National University have combined to form a special moonrock trail in Canberra with displays and rocks from the moon on loan. Details can be found here.

- As well as planting the American flag on the moon, the astronauts left a plaque that said: “Here men from the planet earth first set foot on the moon, July 1969 A.D., We come in peace for all mankind.”

- Buzz Aldrin took a slice of bread from home to take communion on the moon.

- The first meal on the moon eaten by Armstrong and Aldrin with a fork and a spoon was beef and potatoes, butterscotch pudding, a chocolate brownie and grape punch.

- If the astronauts hadn’t made it back to earth, President Nixon had a prepared speech to read about how the astronauts “sacrificed their life to help mankind and that they will be left on the moon and all radio contact to them cut off as they lie on moon – and the command module will fly back”. The speech was made public 30 years later.

- In 1964, five years before the moon landing, Pan American World Airways started selling space flights with the intention of launching commercially operated passenger flights. Would-be customers put down their names on a waiting list, joining Pan Am’s “first moon flights” club. Pam Am ceased operations in December 1991 and those moon flights were but a pipe dream.

- In 1988 Edwin Aldrin legally changed his name to Buzz Aldrin after being known by that name from an early age after his sister Fay Ann, at a youngster called him buzzer instead of brother.

VIDEO: The original mission video of the Apollo 11 astronauts conducting several tasks during extravehicular activity operations on moon from NASA’s YouTube channel.