This story first on the role of the flight simulator in pilot training appeared in the August 2019 edition of Australian Aviation.

The power of preparation is a familiar theme in aviation. The hours of work undertaken on the ground can greatly improve the quality of the flight hours that are logged. While there are many aspects of preparation, the flight simulator has evolved over the decades to provide a critical component in the training environment, its use being not only cost-effective but able to prepare pilots for a host of situations that they hopefully will never have to face in the air.

Seeds of learning

As far back as the early 1900s, flight simulation came into being. An early French simulator placed the student pilot in a specially designed barrel. The instructor would fundamentally position the barrel about its axes and the student would have to correct the barrel back to level flight. This was followed by other various mockups to train fledgling pilots until a major leap forward came in the late 1920s with the emergence of the veritable Link Trainer, although it would be a few years before its value was truly appreciated.

A pitching, yawing, rolling device with stumpy wings and a disproportionate empennage, the lone student occupied the cockpit while an instructor worked from a nearby table. Motion was generated by bellows, originally from an organ, and the instructor could watch a charted plot at the table and transmit calls to the student. Through WWII the Link Trainer was used around the world and in later years as the General Aviation Trainer, or GAT, it was the first taste of flight simulation for many of today’s senior airline pilots.

Flight simulators as airlines know them now emerged in the 1950s, providing replication of specific flightdecks rather than generic cockpits. Through the decades, the generation of visual displays and motion evolved to a highly realistic state such that pilots could become endorsed to operate an aeroplane that they had never actually flown.

Today, the range is far and wide. Home computers can be adapted to provide amazing feats of simulation and while military simulators might not be able to simulate the G-forces, some such as the Pilatus PC-21 simulator can inflate the pilot’s G-suit to offer them a subtle reminder. And with the rapid development of virtual reality, or VR, one can foresee simulation entering an entirely new era once again.

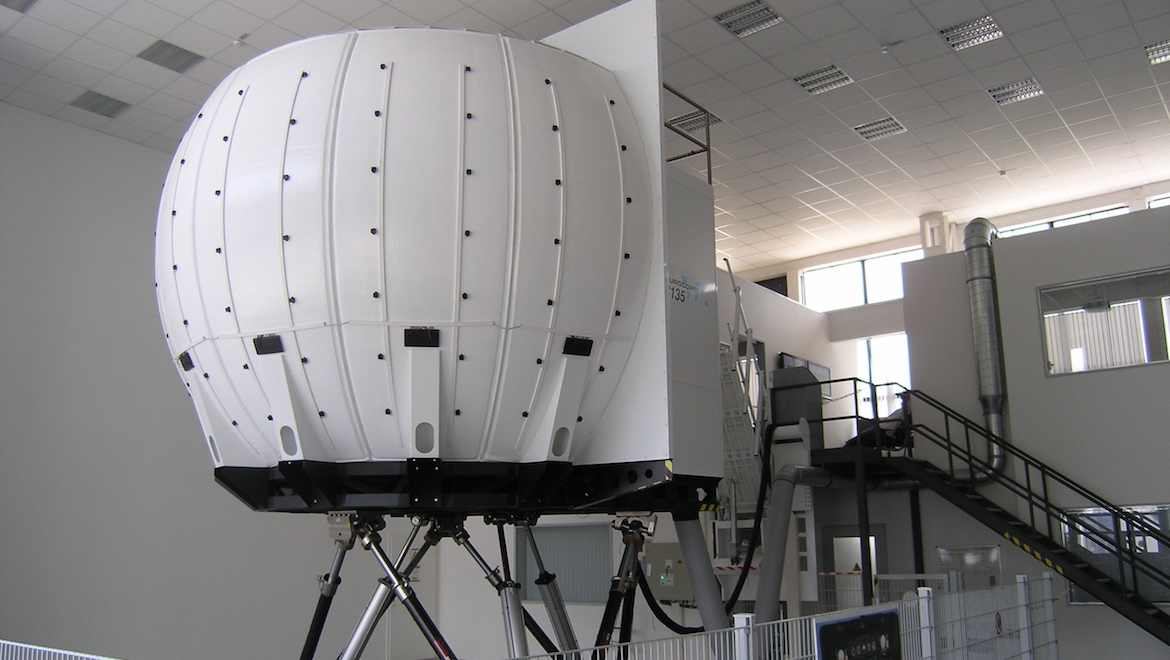

While the technology may be amazing and “visuals” incredibly realistic and attention-grabbing, at the core flight simulators are training devices. To the onlooker they be a source of wonder. To airline pilots, the perception can range from incredible asset to a modern-day torture chamber – depending on the day.

On the way up

In pursuit of an airline career, it is likely that a student pilot will encounter some form of flight simulation – from a desk-mounted aircraft instrument panel with pedals beneath, to advanced personal computers and commercially available programs that can be tailored to individual aircraft types.

The range is broad with each level offering more and, in turn, requiring a higher level of certification when used in the training realm rather than the home. From the more basic flight training devices (FTD) through to the top of the tree Full-flight simulator (FFS), different levels of certification recognise the realism and fidelity of the device. Accordingly, within that certification comes differing levels of recognition by the regulator for the skills acquired. At the highest level, a complete type endorsement can be achieved through simulated flight alone.

Most airline candidates will first experience a Full-flight simulator when they undertake the simulator check for entrance to an airline and. even then, there is the possibility that the simulator will not utilise its motion and be “off the jacks”. For some, strapping into a realistic airline flightdeck can be daunting in itself, but to then fly an unfamiliar type can border on nerve-wracking with a potential career on the line. The good news is that the airlines are realistic in their expectations and are looking for improvement as the session progresses as much as the standard attained. From this viewpoint they can assess the candidate’s potential to learn.

If successful, the ground training element of an aircraft type endorsement may be filled with a range of flight training devices and simulators, from the simplest to the most complex. A long-established staple of the training process is the most basic of procedural trainers, sometimes referred to as a “Bamboo Bomber”. Often tailored from wood, with an overhead and forward flight panel and centre console, photographs or diagrams of the various switches and instruments are attached to loosely resemble a flightdeck. Garden variety office chairs can be placed in the positions of captain and co-pilot and from there, students can practice their procedures, touching the “switches” and verbalising the appropriate checklists and calls.

Over the years, the Bamboo Bomber has evolved and where diagrams were once posted, digital images exist. Many of these possess touchscreens which in turn can action a switch, with the appropriate movement of that switch and the associated light or message appearing – something that a one-dimensional picture could never achieve.

Similarly, there are Flight Management Computer (FMC) training devices that allow the student to initialise the FMC and perform various enroute functions as well. These can take a variety of forms, from a computer program moving the cursor, to a fully-fledged FMC, sometimes connected to a display representing the programmed flight. Others are integrated into a procedural trainer, forming a very complete fixed-base training device.

Hours spent practicing procedures with a fellow trainee, or “Crash Buddy”, are hours well spent. By embedding the procedures, checklists and language, along with the crew co-ordination of the multi-crew operation, candidates will avail themselves of more “brain-space” when they move onto the Full-flight simulator.

The first exposure to a Full-flight simulator beyond the initial airline selection process is often with an engineering perspective. Conducted without “motion”, the sessions can examine various aspects of the aircraft systems and how they behave when switching takes place. This training can be conducted in parallel with further practise of the all-important procedures.

By the time students enter the simulator to learn how to “fly” it, they should be well-versed in the aircraft type, its systems and procedures through their previous ground training. Even so, the training will be a gradual process along the syllabus guidelines as certain items become second nature and others require more work. As with all training, there will be peaks, plateaus and troughs in performance and just like simulator sessions themselves, they are part and parcel of an airline career.

After weeks of ground school and hours training on devices, procedural trainers and simulators, the final simulator check will mark a major milestone in an airline career. From there, the training in the aircraft, “on the line” will generally commence. The advancement of simulators, among other factors, has meant that for many airlines, “base training” in the actual aircraft no longer exists. There was a time when newly checked out pilots would fly to an airport such as Avalon (YMAV), void of passengers, and fly circuits and simulate an engine failure after takeoff (EFATO).

With or without base training, the ground school has been completed. However, the flight simulator will remain central for an entire career.

A permanent fixture

Even when a pilot has checked to line and is flying as a fully-fledged crew member, training remains a constant element throughout an airline career. In addition to ongoing training, there is the requirement for pilots to be periodically “checked” to ensure that they are maintaining the required standard of operation and not allowing bad habits to creep in.

Fortunately, the philosophy surrounding these periodic reviews has changed for the better over the years with genuine emphasis on the training benefits being the norm today. The advent of crew resource management (CRM) and human factors training within airline culture has shown the benefit of training in a positive environment rather than beneath the shadow of a big stick. That is not to say that standards have dropped; it is merely a recognition that simulators are wonderful training tools and should be used as such. Additionally, it is no secret that information can be assimilated better and performance improved in more conducive surroundings.

Typically, a routine simulator session will comprise of both checking and training elements with captains and co-pilots being called to operate both as the pilot flying (PF) and in a monitoring role, or pilot not flying (PNF). The scenarios can take place at ground level, or altitude, and at any airport to cover the syllabus requirements. Sometimes there’s a need to take a breath between exercises to remember which pilot is flying the next sequence and where it is taking place as the session hops between items.

Beyond the regular periodic sessions, simulators are used for Line Orientated Flight Training, or LOFT. In LOFT, the flights are in real time, from start to stop and not moving from one scenario to another. Flown as a sector, there will inherently be an issue or two that needs to be resolved – anything from a systems issue to a sick passenger, or both. The emphasis in LOFT is observing how the crew operates, communicates and makes decisions, examining the application of CRM and other human factors.

Increasingly, simulator checking and training is being tailored to the individual, or an aircraft fleet, generally known as evidence-based training (EBT). Under this system, aside from the mandatory items, the training component focuses on areas where data gathered from personal past performances, line operations or even global statistics, indicate a pilot could benefit from further training. The system recognises that a one-size-fits-all template may not always yield the best training benefits. Furthermore, the data that emerges from accident investigations around the world can be compiled and built into a simulator flight profile. Through this, crews can not only witness the event from the pilot’s seat but go about identifying the various stages of an accident and applying possible solutions.

Another significant advantage of a simulator over the aircraft is the ability to pause and repeat. A manoeuvre or scenario can be paused in mid-air, allowing the training pilot and the crew to discuss the item as it develops. Additionally, the simulator can be repositioned back to the start of the scenario and reflown to completion any number of times.

As a pilot moves on through their career, the simulator remains a constant companion. In simple terms, it may provide revalidation for a pilot returning from extended leave. When the time comes to change aircraft types, or upgrade to a higher rank within the system, the simulator will be a core element in the process. Yet, even though simulators are magnificent training aids, they are not always thought of in glowing terms.

The box. Heaving or helpful?

One of the foremost benefits of flight simulators is the ability to practise a vast range of scenarios that cannot, or should not, be replicated in the real aircraft. Everything from an engine failure on takeoff, to “jet upset” events at altitude, engine fires, stalls, rapid depressurisations – the list goes on. With absolute safety, crews can rehearse for events that they will most probably never encounter in their career but retain the ability and skills needed to counter them should the day unfortunately arrive.

As these are relatively rare events, they are not seen in day-to-day operations. And while pilots maintain their memory checklist items and routinely review such events, the requirement to perform the procedures under scrutiny can lead to a level of stress and pre-simulator nerves for some pilots – particularly if they perceive that their licence is “on the line”.

Rather than a training aid, in these cases the simulator can be seen as a heaving box atop its articulated legs, sent to torture the unwary. However, as with any other aspect of aviation, sound preparation goes a long way to dispelling such levels of stress. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the broader training culture is far more positive than some decades ago and pilots will more frequently exit the simulator having learned from the process rather than merely having survived. Still, for some, simulator checks are a dreaded but necessary aspect of the profession.

Even the best prepared candidate can face some compelling challenges during a “check ride”. The realism of the simulator can be immersive and for all intents and purposes the events can seem to be real to the pilots. Adrenalin can flow and heart rates can rise and again simulators are proving beneficial in preparing pilots for the inevitable “startle factor” when an emergency takes them by surprise. The startle factor is also known as the “amygdala or limbic hijack”, which refers to a region of the brain, and is a physical and mental reaction to sudden stimulus which instinctively challenges us to fight or flight. Its presence can impede our rational thought and function until the balance within the brain returns. While the body’s responses are instinctive, repeated training and exposure has the potential to navigate crews through the initial startle safely and perform their duties as needed.

The simulator will always be a source of stress for some and just another day at work for others. However, universally, the benefits undoubtedly outweigh the periodic angst felt by some and are crucial in maintaining a high standard of operational readiness.

Not quite flight

From the quiet enthusiast with a home computer to the advanced Full-flight simulators, the ability to replicate flight scenarios has revolutionised aviation, whether through new insights to the individual, or as a critical tool in an airline operation. With each generation, the fidelity and realism moves forward, allowing the most unlikely events to be flown time

and again.

Perhaps virtual reality (VR) will further expand its presence into the world of flight simulation and offer even more training options. For now, whether the Bamboo Bomber, a Full-flight simulator or virtual reality, the benefits of sound preparation, visualisation, practise and repetition will always be of benefit to pilots.

Like, love or loathe them, flight simulators offer a safe, cost-efficient means of training and maintaining a well-prepared pilot. From induction to retirement, the simulator is part of an airline pilot’s life. With luck, they will never be called upon to face the spectrum of emergencies they encounter in ground training, but should luck be against them, their time in a flight simulator will undoubtedly play a pivotal role.

VIDEO: A look at some of the scenarios that can experienced in full-motion simulator from Stefan Drury’s YouTube channel.

This story first appeared in the August 2019 edition of Australian Aviation. To read more stories like this, subscribe here.