From 31,000 feet Antarctica emerges ambiguously on the horizon. At first one questions whether it is a cloud bank but soon the distinct and jagged profile of mountains put paid to any queries. As the Boeing 747-400 speeds towards Cape Adare, it is a far cry from the wooden vessels that crept through the frigid waters in 1841 to first sight and name the peninsula. And while the craft may have changed, the landscape that looms ahead has retained its unchanged majesty.

A fascination with a frozen continent

With sea vessels required to cross vast distances through frigid waters and pack ice, flight offers both a speedy and comfortable means of commercial transport to view Antarctica. This was recognised more than 60 years ago when, in 1957, the first commercial Antarctic charter flight took place with a Pan-American Boeing 377 Stratocruiser landing at McMurdo Sound.

In 1977, the first Qantas aircraft, a Boeing 747-238B, was chartered by Australian businessman, Dick Smith, and flew out of Sydney under the command of Captain Ken Nicholson. The Qantas Antarctic charters continued until early 1980 when they ceased in the aftermath of the Air New Zealand accident at Mount Erebus.

The flights resumed on New Year’s Eve 1994 when Antarctic Charters Pty Ltd (then known as Croydon Travel) began their association with Qantas, flying six flights that first season. 25 years later the two companies are still working together to fly passengers over the planet’s southernmost continent.

Despite its remote location and inhospitable environment, it is a region that continues to provide a wealth of scientific data to researchers on the ground and a sense of wonder to airborne tourists alike. And on closer examination, some of its data is impressive.

Covering 14 million square kilometres Antarctica is nearly twice the size of Australia and accounts for 90 per cent of the world’s fresh water in the form of ice. This ice covers more than 99 per cent of the continent with an average thickness of 2,000 metres and only the coastal rocky outcrops and rising mountain peaks escape the ice sheet. Its average elevation of 2,300 metres makes it the highest continent on earth, the coldest with a recorded temperature of -89.6C and the windiest, with gravity-assisted katabatic winds hurtling down the slopes at up to 320 km/h. The minimal amount of moisture received by the polar plateau compares to the driest deserts on earth.

Antarctica is a unique place and while its mystery and majesty draws scientists and tourists, it also calls for a range of additional considerations for aircraft venturing into the region.

Mastery in planning

The Antarctic charters departed from, or operated into, Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart and Perth and for the most recent season the newly extended runway at Hobart became capable of operating the Boeing 747-400. Adelaide and Brisbane also operate flights, generally every second year. The flight schedule is planned a year in advance and the crews that operate the service attend specialised briefings.

In his role as Antarctic Charter Co-Ordinator, Captain Greg Fitzgerald oversees the flights and it is a role that covers every imaginable aspect of flight operations. From navigation to airspace requirements, crew briefings to onboard camera equipment and the all-important meteorological updates – these are just some of the many strands that need to be drawn together before the Boeing 747-400 ever leaves the ground.

Seated in a meeting room in Qantas’s main Sydney office building, Captain Fitzgerald reviews the main elements of the operation with each crew member, assisted by members of the Qantas Meterological meteorological team and flight dispatch. Each pilot has already thoroughly studied the dedicated Antarctic manual in advance, but the meeting offers the opportunity to reinforce the salient points.

The nature of the environment is unlike any other into which the airline operates. There are peaks reaching 16,000 feet, although the highest mountain in the potential area of operations is Mount Minto which towers at 13,600 feet. Consequently, the Lowest Safe Altitude (LSALT) for operations is a significant consideration. Additionally, altimetry in the region is based on the United States transition level of Flight Level 180 and given the extremes of temperature, cold temperature corrections are applied to the QNH.

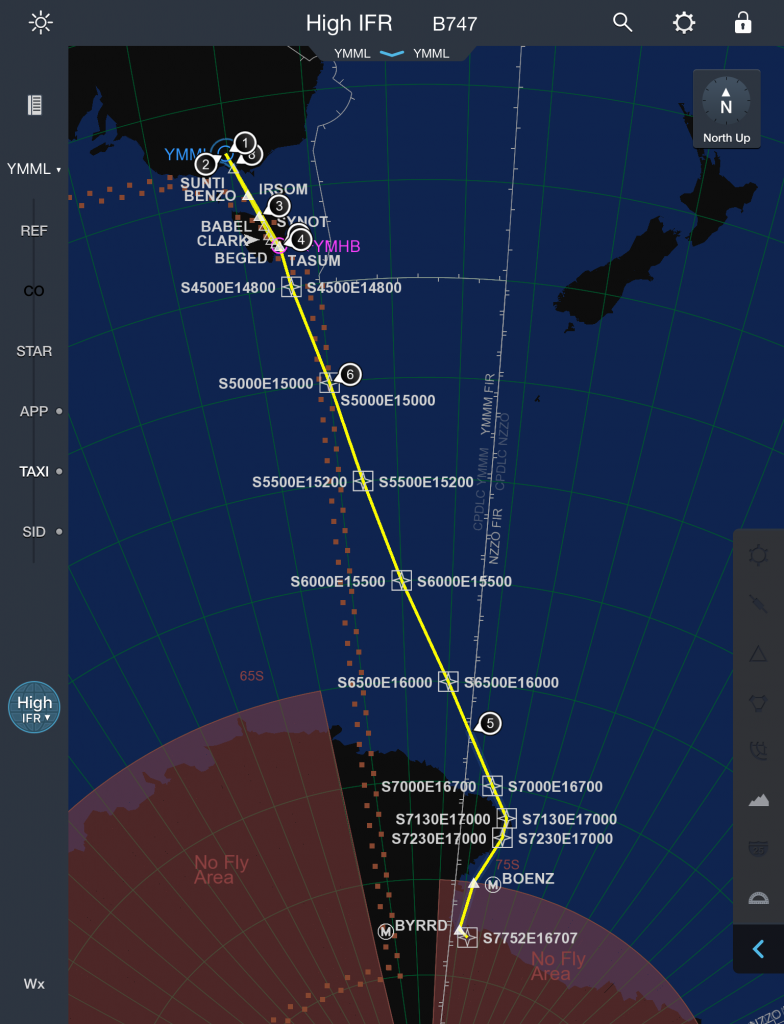

Furthermore, just as altimetry requires special attention, so does navigation which normally uses magnetic North as its reference. Throughout the flight GPS allows a precise track to be flown, however, the heading reference of the aircraft is switched from magnetic to true as the 747 passes 60 degrees South. Less technical, but equally vital, are a series of topographical ‘strip maps’ which add to the overall situational awareness of the crew.

Communications are primarily through (Controller Pilot Data Link Communications) CPDLC and Australian, New Zealand and United States airspace all come into play. Additionally, contact is made with McMurdo station approaching the scenic viewing area and Traffic Information Broadcasts by Aircraft (TIBA) are made on schedule over Antarctica.

As safety is the prime consideration in all flight operations, the importance of a positive handover-takeover procedure between pilots is reinforced to ensure that one pilot is always maintaining a positive watch over the aircraft. And while this may seem self-evident, such amazing scenery as the pilots will witness requires positive cockpit discipline to avoid any lapse in monitoring the aircraft’s flightpath with reference to the instruments.

Even when the briefing has concluded a constant flow of communication circulates between the Antarctic pilots in the weeks leading up to their particular flight. The meteorological data and preflight information for each charter is shared, as is a debrief for each journey south. Through this dissemination of information, each pilot’s insight into the charter flight grows, as does the depth of knowledge and experience for the airline.

Final Preparations

Well in advance of the day, the aircraft for the flight is identified and specifically tracked through the maintenance system to avoid any technical issues on the day. Additionally, the aircraft is required prior to departure to be fitted with specially approved camera and inflight audio equipment which will permit specialist commentary to the cabin on the day and footage to produce a DVD.

The day before the Antarctic charter is to fly from Melbourne, the crew gather in the Sydney meeting room again. Captain Martin Buddery, who is commanding the flight, First Officer Andrew Packwood and Second Officer Mitch Clarke are once again joined by Qantas meteorological and flight-planning briefing officers. Like the Boeing 747, Captain Fitzgerald is already in Melbourne and participates in the briefing via a conference call.

The flights from Melbourne have three predetermined routes, each passing over Tasmania but each making landfall at Antarctica at a different point. From that point, the aircraft will leave the route and subsequently operate in a broader area over Antarctica. The meteorological forecast is particularly important as it aims to identify the most suitable region for viewing based upon the predicted cloud cover and conditions. The means by which this area is identified is both technically interesting and traditionally accurate.

Compiled in a ‘T-36 hours’ printed package, a wealth of information is available to the crew, supported by face-to-face briefing by QMet’s Pete Dawson and Flight Dispatch’s Michael West. Opening with a plain English appreciation of the synoptic situation and a recommended route based upon those conditions, the package includes Terminal Area Forecasts (TAF) and pictorial presentations outlining various analyses and forecasts including cloud cover, winds and significant weather.

Central to the planning and meteorological briefing alike are the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts, or “EC” model, and the Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System, or “AMPS”.

The “EC” model is used extensively in Australia and world-wide as one of the major sources of numerical guidance in support of forecasts for aviation and the provision of meteorological services in general. Based in the UK, the ECMWF produces operational ensemble-based analyses and predictions that describe the range of possible scenarios and their likelihood of occurrence. The forecasts cover timeframes ranging from medium-range, to monthly and seasonal, and up to a year ahead. As used by QMet, it is produced four times daily and has proved to be of great value in providing guidance for the Qantas Antarctic flights over many years. The EC model presents a pictorial cross-section along the route with data such as air pressure, temperature and relative humidity from sea level to the upper atmosphere. Consequently, it is a useful tool in ascertaining cloud cover.

The Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System — AMPS — is an experimental, real-time numerical weather prediction capability that provides support for the United States Antarctic Program, Antarctic science, and international Antarctic efforts. AMPS produces numerical guidance from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model with twice-daily forecasts, specifically covering Antarctica. It is a detailed, high-resolution, four-dimensional structure of the Antarctic atmosphere, where the fourth dimension is time. For the QANTAS flight operations, it is particularly helpful in calculating the lowest cloud base.

With the information presented, a tentative plan is agreed upon to track to Cape Adare to commence operations in the surrounding area as overcast cloud above the Ross Ice Shelf suggesting that area will not be suitable.

With the aircraft at the ready, the meteorological situation reviewed, and a provisional flight plan agreed upon, the meeting is concluded, and the crew make their way to Melbourne for the day that lies ahead.

Bound for Antarctica

It’s not yet quite 5am as the day begins for the crew. In Sydney, Flight Dispatch and Pete Dawson at QMET have already been busily gathering the latest data to relay to the crew as evidenced by the prompt that appears on their iPad when it is brought to life. The flight plan and latest weather forecasts are available, and everything seems in line with the detailed briefing of the day before.

As the bus moves through the dark and silent Sunday morning streets of Melbourne, Captain Fitzgerald discusses the weather once again with QMET’s Peter Dawson on speaker as the rest of the crew listen in. The plan remains and the route towards Cape Adare is confirmed for the best viewing while the land to the south towards McMurdo appears to have substantial cloud cover.

The glow of iPads is the only illumination as the bus makes its way to the airport. The latest briefing material has been uploaded as well as the flight plan which includes an additional detail in its ATC flight strip — the maximum viewing time over Antarctica. By the time the crew is seated in the domestic terminal’s briefing room – yes, this is a domestic service — all of the information has been reviewed and the discussion fundamentally reinforces the anticipated plan and considers the critical differences of the Antarctic operation one more time.

The engineers call to advise that the Boeing 747-400 VH-OEG has been fuelled to its maximum capacity of just over 178 tonnes, given the current Specific Gravity (SG) of the fuel. They also confirm that the aircraft has been fitted with the additional audio-visual equipment and the paperwork has been completed.

Aside from the digital flight plan, there is additional paperwork to be completed for the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in Hobart. AAD is the government department that approves Qantas to conduct these flights over Antarctica, based on environmental impact studies that Qantas supplies and logs that will be kept during actual flights. The Antarctic Flight Summary and Environment Log will be filled out in real time beyond 60 degrees south latitude and submitted to AAD post-flight.

The pilots then make their way down the hallway where Captain Buddery addresses the Cabin Crew for the flight. There is a tangible level of excitement among the crew who are a mix of senior flight attendants and relative newcomers but who all share a common fascination with the flight that lies ahead.

There is still well over an hour until departure and the gate lounge is full of excited passengers ranging from school students to a pair celebrating their ninetieth birthdays. Each with a name tag on their chest and vying for a photograph with the Penguin mascot, there is no mistaking that this is not your everyday Regular Public Transport service. Even with a comfortable margin of time until the Boeing pushes back, the crew is busy readying the aircraft inside and out. This includes confirming the operation of the specially fitted entertainment system and that it is in working order throughout the cabin.

As the sun edges above the horizon in the east the last door of the 747 is closed and all is ready for the journey southward.

Flight of a Lifetime

At 406,000 kilograms, the aircraft is still more than 6,000 kg under its maximum takeoff weight. Under Captain Buddery’s hand it lines up on Melbourne’s Runway 34 and is given takeoff clearance. With the clearance confirmed by the entire crew, the thrust levers are advanced and the four-engined giant begins to accelerate. At 173 knots the Boeing is rotated, lifting its nose from the runway to begin its climb into the morning sky.

The air is smooth as the four-hour sector to the ice begins. Extensive overcast lies below and Tasmania only peeks through a break as the 747 passes overhead. There is a rare opportunity for the members of crew to mingle with the passengers and answer a constant stream of questions about the 747 and the flight details. Interestingly, the pilots have questions of their own for the young PhD students from the University of Melbourne.

Stationed by one of the doors the scientists have set up a range of equipment to conduct experiments relating to cosmic radiation and the earth’s magnetic field. And while they were impressed by the GPS’s read-out of over 300 kmh during the takeoff roll, it one of their instruments that is particularly impressive — the ‘Dip Circle’.

Measuring around 15cm in diameter, the brass ring possesses a dual face of glass with a needle inside. It resembles a large, see-through compass and is designed to measure the vertical component of a magnetic field — or ‘dip’. Made in the 19th Century, this piece of scientific craftsmanship has journeyed to Antarctica before, by boat in 1910.

It is appropriate that science takes its place on board as Australia’s association with science dates back to 1886 when an Australian Antarctic Committee was founded. Today, Australia has three permanent scientific research stations located in Australian Antarctic Territory — Mawson, Davis and Casey. In total, there are 40 permanent research stations in Antarctica conducting valuable research under the truly international banner of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, or SCAR.

Enroute, a phone patch has been organised for Captain Fitzgerald to interview the Casey Station Leader, Christine “Chris” MacMillan which is broadcast through the cabin. In a fascinating exchange, Chris informed the passengers on various aspects of life at an Antarctic Research Station. How the 120 crew is scaled back to just 30 in the winter months, the importance of working as a team and recreational activities which even included a dip into the icy waters on Australia Day.

With two hours remaining until reaching the Antarctic continent, the crew are busy with a range of duties. Critical fuel calculations and maximum viewing times are confirmed, contact is made with McMurdo station, an updated briefing is obtained from QMET and the latest QNHs are gathered from various bases in Antarctica, with the most conservative being chosen for altimetry purposes when the aircraft descends. And that time is approaching.

Land ho!

Passing 60 degrees South the crew commences their additional logs, ensures that the topographical strip maps are at hand and switches the 747’s heading reference from Magnetic to True as the deviation between the two becomes too great nearing the South Pole.

The cloud cover slowly starts to break up below and then ‘Land ho’. In the distance, jutting up are the jagged peaks of Antarctica. With the QNH, viewing time and critical scenarios double-checked, the aircraft begins its descent to a Minimum Safe Altitude of 18,000 feet. McMurdo has advised that the LC-130 aircraft that was inbound has returned to Christchurch due to a technical issue, making the 747 the only aircraft in the area. Even so, reports are routinely made by CPDLC and broadcast on VHF radio.

Spectacular Views During the Flight (Michael Shen)

Towering Mount Minto comes into view and the sheer enormity of Antarctica becomes apparent. Landfall is made at Cape Adare as planned before a short westbound leg is flown, but it becomes apparent that the meteorological team were correct, and a cloud bank lies along that route. Turning back towards the Transantarctic Mountain Range, the view is spectacular and made even more so by the pristine air.

There are mountain peaks and razor-edged ranges, glaciers at every turn. Some of these are filled with reef-like lines of blue ice which forms when snow falls on a glacier and becomes compressed, squeezing out air bubbles and allowing the ice crystals to enlarge. Beyond the coast the water is partially covered by pack-ice with mammoth mesa-like icebergs rising from the sea while their greater mass lurks below.

An ‘ice tongue’ extends out onto the water’s surface where the glacier’s momentum carried it beyond the land mass. Nearby, a patch of brown clearing is the site where the first men, Norwegians, spent a night in Antarctica in 1899. Their hut remains, a silent witness to a bold age of exploration. With every turn there is something new — either just off the wing or extending far past the focus of the human eye.

All the while, expert commentary is provided through the cabin by Mike Craven, a scientist who spent a significant period of time in the region. Fascinating facts from the findings of 3,000-metre-deep ice cores to Patagonian dust and the formation of snowflakes. In the cabin, the excitement and chatter doesn’t cease. Fingers point and smiles beam as one bucket list after another is kicked over. The seating arrangements are reorganised halfway through the total viewing time of three hours and 40 minutes to share vista.

On the flightdeck the view is also appreciated but still the crew attend to their duties with discipline and discuss where may be the next area to investigate. Logs are completed, broadcasts are made, and calculations confirmed. The cycle of activity continues.

The passage of time is rapid over this timeless continent and soon it is time to depart. The intentions of the Qantas Boeing 747 are transmitted, and an airways clearance is sought. There is one last wave farewell to Cape Adare before the climb back into the flight levels begins. Qantas 2907 sets a northerly course and heads for home.

Another World

The sun sets as Bass Strait slides beneath. Many of the passengers are now asleep with the return flight having been less dramatic than the scenery they had witnessed. However, by the time the aircraft has parked at the gate, their enthusiasm has returned and one after another they file onto the flightdeck. Smiling from ear-to-ear, some are as enchanted by the flightdeck of the ‘Queen of the Skies’ as they were by Antarctica. Without exception, the passengers are abuzz and although it has been a long day, the crew attend to them one by one and reflect the excitement that they express.

Buzz Aldrin had a turn of phrase to describe the moon when he set foot on the surface in 1969. It captured the amazement of an expanse, untouched by man and almost overpowering in its enormity. It is a phrase that may well suit Antarctica and be uttered by those that have witnessed it from the skies. Magnificent Desolation.