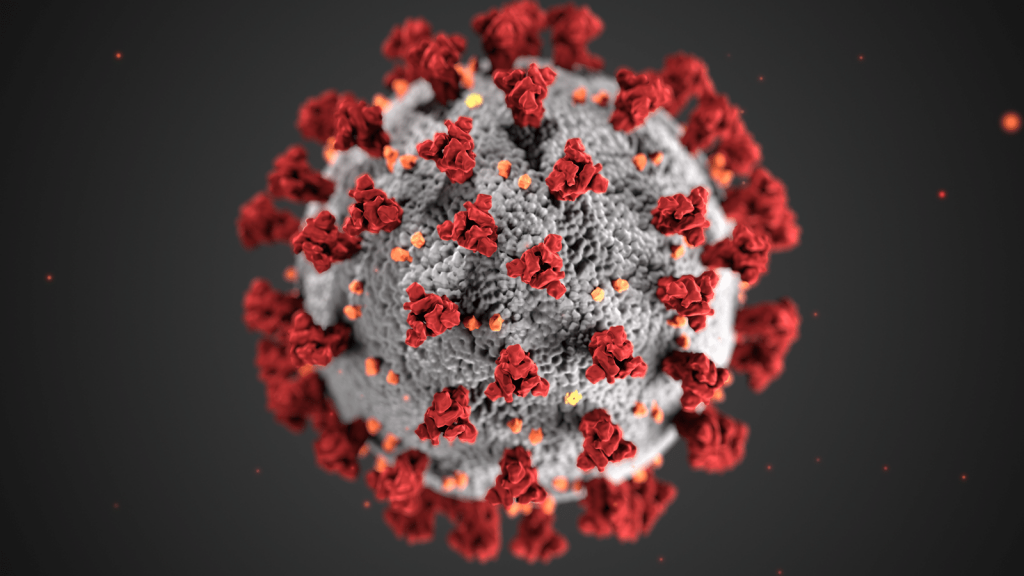

2020 has without a doubt brought about the single biggest disruptor to the global aviation sector potentially ever seen: the COVID-19 pandemic.

2020 has without a doubt brought about the single biggest disruptor to the global aviation sector potentially ever seen: the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 31 December 2019, Chinese authorities officially revealed they were treating a small number of citizens suffering from a mysterious illness in Wuhan. No one knew just what this would mean for the international community in the months to come.

Join us here at World of Aviation in reminiscing and recounting the year that the aviation industry will never forget.

JANUARY

The month of January was quite prophetic for US planemaker Boeing; it was a mixed bag of highs and lows.

At this point in time, the planemaker was already in murky waters, after its once-profitable 737 MAX had been involved in two fatal crashes that killed 346 people. By January, the plane had already been grounded in most regions around the world for nearly a year.

In late January 2020, the first Boeing 777X successfully took to the skies for the first time in front of thousands at Paine Field in Everett, Washington, USA.

The three-hour, 51 minute maiden flight of WH01 was heralded a success and exercised the airplane’s systems and structures, monitored in real-time by the team based at Seattle’s Boeing Field.

Captain Van Chaney, 777X chief test pilot labelled the day’s testing as “very productive”.

And yet, just days later, Boeing released its full-year results for 2019, in which the planemaker posted a loss of US$636 million, its first annual loss since 1997.

The loss compared to the US$10.5 billion profit registered the year prior, which was reported only a few months prior to the second crash of the 737 MAX, and its subsequent grounding.

Boeing also announced this month that it had suspended the production of the 737 MAX, with the platform grounded in March by regulators after the second of two Max crashes.

Meanwhile, Boeing swore in its new president and chief executive officer David Calhoun this month, in another attempt to ride out the PR disaster of the 737 MAX.

At the time, Calhoun said the company had a lot of work to do to regain confidence of customers and the wider flying public.

“We are focused on returning the 737 MAX to service safely and restoring the long-standing trust that the Boeing brand represents with the flying public,” he said.

“We are committed to transparency and excellence in everything we do. Safety will underwrite every decision, every action and every step we take as we move forward.”

FEBRUARY

By the end of January, the outbreak of COVID-19 was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in January 2020 by the World Health Organisation, and by February, the impact of COVID-19 was being felt in the chinese aviation sector.

This month also rang in the Chinese New Year, which is largely considered to be the catalyst for the worldwide spread of the coronavirus.

In this month, World of Aviation reported that 10,000 flights had now been suspended since the outbreak of the coronavirus in China, which was, at the time, a significant disruptor to the local market.

According to travel and data analytics firm Cirium, of the 90,607 domestic and international flights scheduled to operate across mainland China over the six-day period between January 23 and January 28, 9,807 (or 10.8 per cent) did not fly.

Rahul Oberai, Cirium’s managing director for Asia-Pacific, said the outbreak will inevitably cause significant disruption of schedules and travel patterns in the short- to medium-term, however long-term demand would rebound.

“The precedent of the SARS outbreak indicates to us that the underlying demand for travel driven by GDP growth will in time produce a robust recovery.”

The impact of the Coronavirus outbreak also caused China’s share of the global aviation market to slump from the third-largest market in the world, down to the 25th spot by mid-February.

The nation’s airline capacity, defined as the number of seats available to book, has reduced by 1.7 million seats since 20 January, placing it only slightly ahead of Vietnam.

The OAG’s John Grant said in a blog post: “No event that we remember has had such a [devastating] effect on capacity as coronavirus. Ultimately the market will recover, we know that, but in the short term the damage to some airlines and the long-term impact on their growth may linger beyond the virus.”

Singapore Air Show forges on

Elsewhere in the world, The Singapore Air Show went ahead without a hitch, despite the growing COVID-19 health concerns that had now begun to sweep the globe.

The event was opened on 11 February by Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance, Heng Swee Keat, who was joined by Vincent Chong, Chairman of event organisers Experia Events.

Event organisers believed the trade show would attract 45,000 attendees from 45 countries, with delegates representing 930 companies.

However, health concerns and travel bans saw a more subdued occasion, with most Chinese exhibitors and delegates forced to cancel, as well as big-shot names such as Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Honeywell.

Air show organisers said only 8 per cent of overall participating companies have withdrawn from the event.

At this point in time, Singapore had raised its Coronavirus alert status to Orange, the second highest level of its Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON).

Debri found in 737 MAX fuel tanks

February held more bad news for Boeing, after foreign debris was found in “several” grounded 737 MAX aircraft in Seattle, which was flagged as a potential safety risk.

Vice president Mark Jenks told employees the presence of material, thought to have been left behind by maintenance workers, was “absolutely unacceptable”.

The email referred to ‘foreign object debris’, thought to include rags, tools and metal shavings.

Jenks, listed as the company’s vice president and general manager of the 737 program, was forthright in his criticism, reportedly telling staff “one escape is too many”.

He added, “With your help and focus, we will eliminate FOD [foreign object debris] from our production system.”

Airbus Defence and Space feels the heat, while commercial thrives following Bombardier deal

Meanwhile, over in European rival Airbus’ camp, things also weren’t looking great by February.

Airbus announced it would need to cut more than 2,300 jobs from its defence and space division worldwide before the end of 2021.

The company blamed a flat market and postponed defence contracts for the redundancies, but maintained that the underlying outlook “remained solid”.

Meanwhile, other regions of the business appeared less affected by a subdued market.

In February, Airbus completed its negotiations to buy out Canadian manufacturer Bombardier’s remaining stake in the A220 program, raising its on share from 50.1 per cent to 75 per cent.

The deal saw Bombardier exit the civil aviation industry altogether, and bolstered the European planemaker’s position in its ongoing competition with US rival Boeing.

At the same time, CEO Guillaume Faury announced that Airbus intended to invest more than €1 billion in its A220 program in 2020.

Airlines begin to address COVID’s financial impact

By the end of February, China wasn’t the only market feeling the impact of COVID.

At the time, Air France warned that the coronavirus outbreak would affect its profits, estimating the impact on the business to sit between €150 million and €200 million between February and April alone.

The news followed after Qantas made a similar statement, claiming the outbreak would cost it up to $150 million.

Air France-KLM said in a statement, “Assuming a progressive resumption of (full-scale) operations from April, the estimated impact of COVID-19 on operating income is for a €150 to €200 million hit between February and April.”

The warning came after the airline announced a 31 per cent drop in profit to €290 million, which the company blamed on a fall-off in freight and rising fuel bills.

However, Air France-KLM director-general Ben Smith indicated at that time he did not believe the virus would affect the airline’s strategic five-year plan to lift the medium-term operating margin to 7-8 per cent from 5 per cent in 2018.

A week prior to Air France’s announcement, the International Civil Aviation Organisation estimated that coronavirus could cause a $4-5 billion drop in worldwide airline revenue, while Chinese officials announced the death toll from the disease had risen to 2,236, with more than 75,000 reported cases.

At this time, many carriers had halted all flights to and from China until the end of March.

Little did anyone know what was coming next…

MARCH

By now, you probably know by the time March came around, the concern of COVID-19 had grown, and airlines were beginning to really take the hit.

The World Health Organisation officially named COVID-19 as a global ‘pandemic’ on 11 March, and by the end of the month, many countries were entering varying degrees of lockdowns.

Early in the month, airlines around the world had begun to ask their staff to take voluntary unpaid leave in order to alleviate the financial pressure of an internationally subdued market.

Big players such as Emirates, Qantas, Singapore, and EasyJet had all made announcements within the first few days of March.

Meanwhile, on 2 March, United Airlines postponed the start date of 23 of its newly recruited pilots in light of lower flight demand, a symbol of what was to come.

Airlines across the globe began cutting their flight schedules, as demand for international travel plummeted, and travel bans began to take hold.

On 5 March, World of Aviation reported that new figures released by the International Air Transport Association for January showed the slowest traffic growth since 2010’s volcanic ash crisis.

Alexandre de Juniac, the organisation’s chief executive, warned the worrying figures were just the “tip of the iceberg” because most coronavirus travel bans didn’t start until the end of the month.

He said, “Major travel restrictions in China did not begin until 23 January. Nevertheless, it was still enough to cause our slowest traffic growth in nearly a decade.”

At that time, De Juniac warned that there was more to come.

“January was just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the traffic impacts we are seeing owing to the COVID-19 outbreak,” he said.

“The COVID-19 outbreak is a global crisis that is testing the resilience not only of the airline industry but of the global economy.

“Airlines are experiencing double-digit declines in demand, and on many routes, traffic has collapsed. Aircraft are being parked, and employees are being asked to take unpaid leave.

“In this emergency, governments need to consider the maintenance of air transport links in their response.”

Soon after, the IATA also revised its expectations of the potential financial impact of the coronavirus on the aviation sector, to be four times as much as previously thought.

IATA then estimated the financial impact to be up to $113 billion if it spreads to previously less-affected markets.

The news comes after the organisation updated its analysis of the financial impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency on the global air transport industry.

De Juniac said: “The turn of events as a result of COVID-19 is almost without precedent. In little over two months, the industry’s prospects in much of the world have taken a dramatic turn for the worse.

“It is unclear how the virus will develop, but whether we see the impact contained to a few markets and a $63 billion revenue loss, or a broader impact leading to a $113 billion loss of revenue, this is a crisis.”

First COVID casualty: Flybe collapses

That same day, on 5 March, we saw the very first aviation casualty of the COVID-19 crisis: UK regional carrier Flybe had entered administration, with all flights immediately cancelled.

While the regional airline had been struggling in the weeks and months prior, it was the outbreak of COVID-19 and its effect on the aviation market that was the final nail in the coffin for Flybe.

Flybe had been rescued from near-collapse in mid-January through government tax deferrals, reduction of air passenger duties, and a cash injection from private shareholders.

Support from Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government recognised the role the airline played in connecting regional Britain, and was meant to underpin Flybe’s stability into the future.

However, soft domestic demand and a falling British pound made business difficult for the Exeter-based LCC, before coronavirus exacerbated its issues.

Europe becomes a COVID hotspot

By mid-March, parts of Europe, Italy in particular, had become a breeding ground for the virus.

European carriers British Airways, Rynair and EasyJet all cancelled flights to and from Italy in an effort to reduce the spread further throughout the continent.

Meanwhile, on 12 March, then-US President Trump banned all flights from mainland Europe from entering the US for 30 days.

Shortly after, Spain enforced a two-week state of emergency that saw at least five flights from the UK turned around mid-flight, and holidays ultimately cancelled.

Around this time, airlines all over the world continued to cut flight schedules, almost entirely. Singapore Airlines said it would cut 96 per cent of its capacity until the end of April, Lufthansa cut 95 per cent, United cut all its long-haul international routes, and Emirates suspended all passenger operations; a decision that it ultimately repealed fairly quickly.

EasyJet ultimately grounded its entire commercial fleet, citing “unprecedented travel restrictions”, by 31 March.

Airlines turn to governments for bailouts

In a desperate attempt to offset cash burn as planes remained grounded and demand hit unprecedented lows, airlines around the world asked governments for financial aid.

The International Air Transport Association called for measures including credit lines, tax breaks and passenger duty deferrals to alleviate the strain on the industry.

IATA director-general and CEO Alexandre de Juniac said: “Without a lifeline from governments, we will have a sectoral financial crisis piled on top of the public health emergency.”

The news came as the French government pledged financial support to embattled flag carrier Air France and hard-hit nations such as China and Korea also promised to assist the sector. Lufthansa had already approached the German government asking for help.

Later, US senators voted to approve a $2 trillion coronavirus rescue package for the country, which includes more than $58 billion in aid for the aviation industry.

At the same time, aviation regulators in the US and EU agreed to relax their airport slot rules to ease pressure on airlines to meet pre-COVID requirements to operate 80 per cent of their allocated airport slots or face losing their slot rights.