The next generation of air combat capability is here. But what comes next?

While the operational arm of the RAAF will be working hard to get the F-35 up-to-speed as quickly and efficiently as possible, Lockheed Martin, the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program Office (JPO) and the partner nations are studying where next to take the F-35’s capability.

Weapons

One of the key priorities for program planners will be to increase the number of weapons available to JSF operators which have many and varied requirements to meet their air combat needs.

Australia, for example, has a requirement to be able to employ an anti-ship missile from its F-35As, a capability that isn’t a requirement for the USAF on their F-35As. To this end, the RAAF is co-funding the development of the Kongsberg/Raytheon Joint Strike Missile (JSM), a development of the surface-launched Naval Strike Missile (NSM). The program promises an advanced internally-carried, air-launched, anti-ship and fixed target missile will be available in the next few years.

Australia will also likely have a requirement in the future to employ a long-range stand-off missile against fixed and mobile targets. The RAAF is already an operator of the 400km range AGM-158A JASSM on its classic Hornets, while the 1,000km range AGM-158B JASSM-ER is likely to also be of interest, as is the AGM-158C LRASM maritime strike version.

New customers

With Belgium recently selecting the F-35A over the rival Eurofighter, the list of foreign military sales (FMS) customers for the JSF grows. Israel is leading the way having already used its F-35As in combat, while Japan and South Korea are gradually growing their F-35A capabilities.

JSF program partner nation Canada will decide on its CF-18 Hornet replacement in early 2020. Despite remaining in the partnership, and Canadian industry continuing to be a major component supplier, Canada’s program has effectively been on hold since the Trudeau government came to power in 2014.

Since that time, Canada has ordered and then cancelled an interim buy of 18 Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornets after a trade dispute with the US, and is now part-way through a competitive evaluation of other types including the Saab Gripen, Eurofighter Typhoon, Super Hornet, and the F-35. Dassault recently withdrew its Rafale from the evaluation after it was unable to meet Canada’s industrial offset requirements.

With a CF-18 replacement unlikely to start entering service before 2025, Canada will take between 18 and 25 former RAAF classic Hornets as they are retired to bolster its own Hornet fleet and spares pool until 2030.

Despite initial cost worries from Canada and concerns about operating a single-engined fighter over Canada’s vast Arctic, many observers believe the F-35 will prevail due to its commonality with the USAF and five-eyes partners Australia and UK, and because the F-35’s growth path will outlive its rivals.

Other possible F-35 customers include Singapore, which has a need to replace its F-16s from mid-next decade and has reportedly shown some interest in a mixed fleet of F-35As and Bs, Germany which is studying a Tornado IDS strike replacement, Switzerland which needs to replace its F-5E/Fs and ageing F-18C Hornets, and Finland which is also looking for a replacement for its F-18Cs. The Trump administration is also reportedly looking at how it might sell the F-35 to Middle Eastern allies like the UAE, despite likely push-back from Israel.

Israel itself will soon need to decide whether to grow its F-35A fleet from the 50 it currently has in service or on order as its ageing F-16s are retired, although it is also looking at an enhanced F-15AI as an option.

On the negative side of the ledger, Turkey’s participation in the program is in jeopardy with the US government’s decision earlier this year to suspend F-35A deliveries and pilot training following Turkey’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 air defence system. The US DoD is reportedly concerned that the S-400 could compromise the F-35’s capabilities.

Italy has also announced it plans to reduce its buy of a mix of F-35As and Bs. Originally planning to buy 131 F-35s, Italy reduced this number to 90 in 2012. But following the election of a coalition government earlier this year which includes a strong anti-military component, Italy’s acquisition rate of 10 aircraft a year was reduced to six, and the total is also reportedly further at risk.

Australia will need to decide in the next few years how to replace the 24 Super Hornets it acquired in 2007 to bridge the capability gap between the retirement of the F-111 in 2010 and the F-35A’s planned full operating capability (FOC) in December 2023. Project AIR 6000 Phase 6 – previously Phase 2C – will consider the acquisition of up to 30 more F-35As to replace the Super Hornets from 2028.

But another option will be to retain the Super Hornets through to a full life-of-type by upgrading them to the planned Block III configuration currently being developed for the US Navy. This upgrade includes structural enhancements to give a 9,000-hour service life, conformal fuel tanks, a new electronic warfare system, an infrared search and track (IRST) sensor, a new DTP-N mission computer and TTNT data link, signature improvements, and advanced cockpit system displays.

Many of these improvements will also find their way on to the EA-18G Growler, and because the Growler is projected to have a full life-of-type with the RAAF into the 2040s, this could bolster the case to retain and upgrade the F/A-18Fs.

Global Supply Chain

The F-35 global supply chain will also be an evolving capability over the life of the aircraft.

Indeed, this evolution has already begun, with Lockheed Martin recompeting the electro-optical distributed aperture systems (EO/DAS) earlier this year. Incumbent Northrop Grumman chose not to compete for the new contract as it could not justify the business case, and Raytheon was awarded the supplier contract for this key sensor with claimed savings of 45 per cent in unit acquisition costs, increased reliability, and a 50 per cent saving on sustainment.

Similarly, the aircraft’s integrated core processor (ICP) has also been recompeted, with Harris Corp being selected in September to become the new supplier of the key component. Savings in the order of 75 per cent per unit are expected, although this claim is in the context of much higher production volumes which have started with multi-year buys of nearly 200 aircraft compared to the previous much lower rate production.

The new ICP will also include open architecture software which will allow for easier integration of new sensors, weapons and other upgrades. Both the new ICP and EO/DAS should be incorporated onto the aircraft from Lot 15 in 2022/23.

At the 2018 Farnborough Airshow, Lockheed Martin’s vice president and general manager for the F-35 program, Greg Ulmer, told media that the company is looking to recompete other key elements which should continue to contribute to reduced acquisition costs and greater sustainment savings.

“It’s good business for us to continually look at our supply and (ask) should we resource or compete that material? We want best value, so as we produce the aircraft we want to make sure we’re producing the material that meets the requirement for the least amount of cost,” he said.

Block upgrades

In the early days of the JSF program Lockheed Martin and the JPO planned to have clearly defined Block capability, mainly comprising software but interspersed with hardware technology refreshes.

But as the program has evolved and the number of low rate initial production (LRIP) lots have extended into the teens, the lines between these enhancements has blurred. This has meant there are many sub-blocks being introduced every few months, much the same way as Apple or Samsung sends upgrades out to their phone users. This has had both positive and negative impacts on the program.

On the positive side, the adoption of such a rapid insertion upgrade model has meant the JPO can now prioritise software and firmware enhancements and address deficiency reports without having to wait for a major block upgrades or tech refreshes.

But this also means there are multiple sub-fleets of aircraft with different software configurations on flight lines as aircraft await their latest software upload.

“From the [software engineering directorate’s] perspective, we kind of did this big bang approach for this big huge final capability release” for block 3F, Greg Ulmer said at Farnborough. “In the future you’re going to see rapid insertion spiral development,” he said, adding that there will be “a lot of updates” in the lead-up to Lot 14, before there is a major technology refresh on Lot 15.

“In Block 4 you will see different releases of capability to the airplane over that horizon,” he said. “We won’t wait for the end for all that to be inserted. We will do it in increments as those capabilities come onboard.”

Block 4 has been re-defined as a follow-on modernisation program, and is scheduled to start next year. It will include yet-to-be-defined capability enhancements, new weapons, and corrections to deficiencies in nine capabilities that have been carried over from the Block 3 development program. These include improvements to the prognostics health management system down-link to autonomic logistics information system (ALIS), and some communications capabilities.

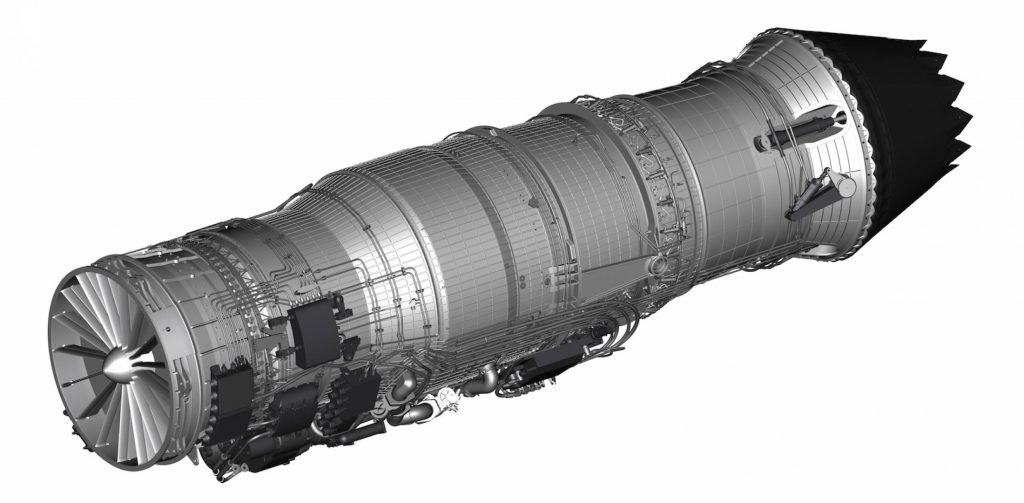

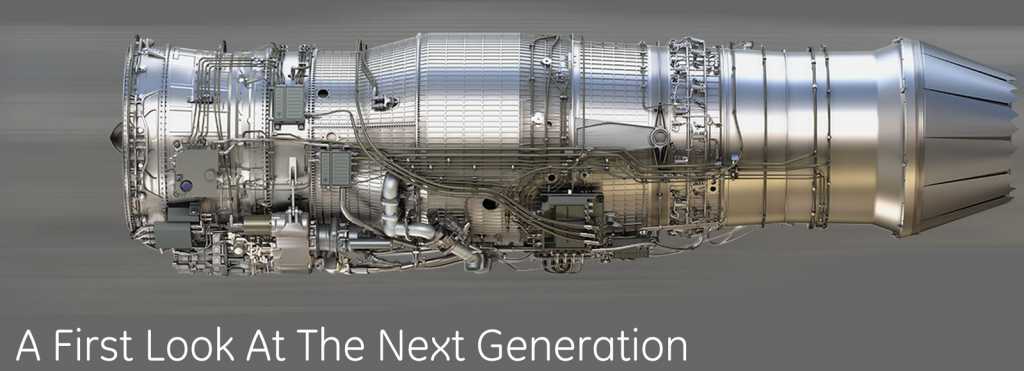

Engine upgrade

Despite being the most powerful production military engine in service, Pratt & Whitney is also looking to add further power and reliability improvements to the F-35’s F135 engine.

The company has articulated a two-staged upgrade path for the F135, labelled Growth Option 1.0 and Growth Option 2.0 which it plans to introduce over the next four years.

The company says it has combined its planned Growth 1A thrust-increase option for the F-35B’s STOVL engine with the Growth Option 1.0 package which will provide a 10 per cent thrust increase and five per cent improved fuel burn.

For Growth Option 2.0, the company will offer an all-new production engine that will incorporate elements of its adaptive-cycle technology developed through the USAF Research Laboratory Advanced Engine Transition Program (AETP). It has been reported that Growth Option 2.0 will provide a significant increase in power and thermal management system (PTMS) capability.

The adaptive-cycle technology focuses on third-airstream capability, adaptive-cycle controls, and new materials, with the company planning to “take the technologies as they mature and insert them into existing engines,” president of P&W Military Engines, Matthew Bromberg told AIN News in September. “It’s a whole suite of technologies; we will look at everything. We’re leveraging the bleed systems, the integration system, and the control system.”

Bromberg also said the company is “…looking at adaptive elements in the controls, the components, and the core”.

Despite losing the original F-35 engine contract to P&W, GE Aviation has also been awarded a contract by USAF to develop its own adaptive-cycle engine. If successful, its XA100 demonstrator or its production development could be a candidate for an F-35 engine recompete contract in the mid-2020s.