There was a time when being first into the market with the latest jet from Boeing or Airbus was a winning formula for progressive airlines. Over the past few years, however, being a prime mover has become a risky and highly costly business as repeated operational glitches plague some of the newest models.

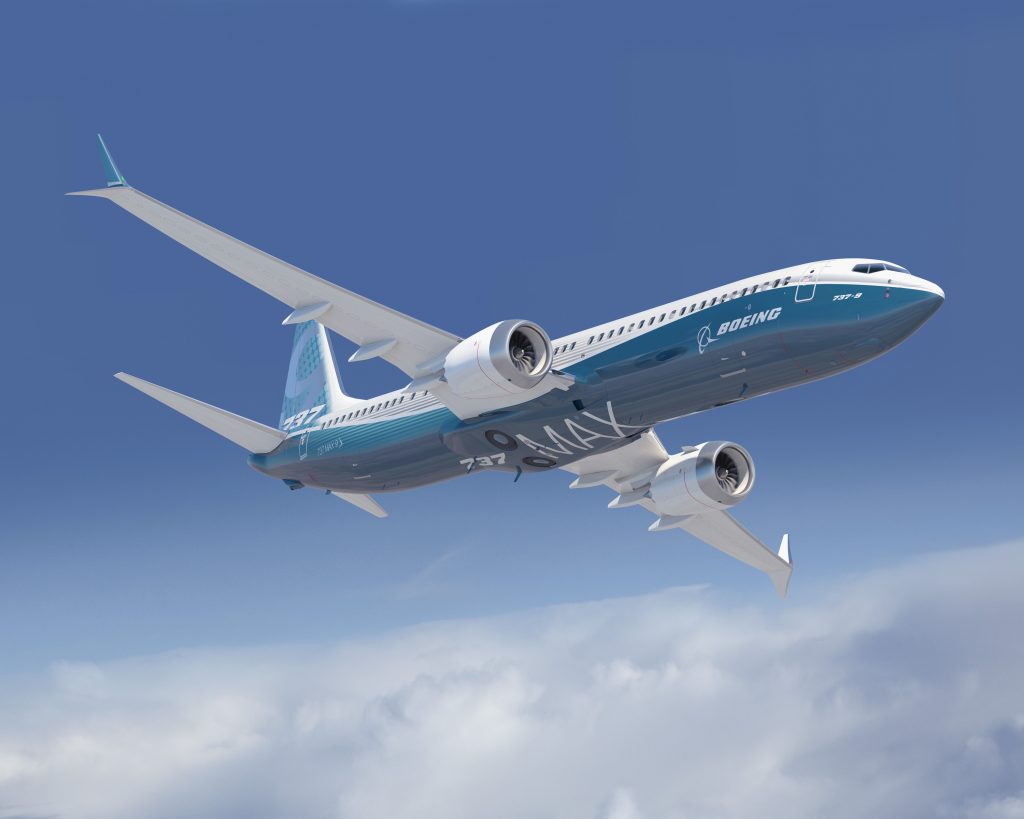

It is the best-selling airliner of all time and the fastest selling in Boeing’s history. Since its debut in 1967 the US manufacturer has gleaned nearly 15,000 orders for its popular single-aisle B737. The latest version, the B737 MAX series, has logged more than 4,700 orders since 2011. Yet in March all the hype about its fuel efficiency and high-tech features came crashing to a halt after the second fatal accident in fewer than five months involving what were, essentially, brand new jets – the first with Indonesia’s Lion Air and the most recent with Ethiopian Airlines, resulting in the deaths of 346 passengers and crew.

Both crashed to the ground just minutes after takeoff under strikingly similar circumstances,

While nations and airlines around the world progressively grounded their MAX fleets – 350 had already been delivered to airlines – and as accident investigation teams and Boeing threw their expertise at pinning down the cause and finding a fix, the spotlight once again was falling on air safety.

Over recent years, problems have plagued the new generation of jets taking to the skies. From early faults with batteries catching fire on the B787 Dreamliner to Rolls-Royce engine issues on the same aircraft and Pratt & Whitney engine problems on the Airbus A320 neo, operators have been dogged by inflight shutdowns and groundings of planes barely off the production lines. While, fortunately, none of these led to fatal accidents, it was a worrying trend in an industry using high-cost assets that are becoming increasingly technologically sophisticated. So much so that US President Donald Trump went so far as to suggest today’s jets were becoming “too complex to fly”.

That may have been another example of Trump over-statement but it does raise questions.

Airlines and their cockpit crew welcome new technology that brings operational efficiency, fuel saving and longer-haul flying, but what happens when the technology goes wrong? Are pilots becoming too reliant on the computerised cockpit and losing basic flying skills? Are new aircraft and their engines, as well as the hardware and software inherent in their design, being flight tested sufficiently before entry into service?

Experts are unanimous. No matter how rigorous the months of flight and ground tests on airframes, engines and technology conducted prior to certification, the stresses of daily commercial operations can’t be entirely replicated. A case in point, says Sydney-based Professor Ron Bartsch, chairman of consultants AvLaw International, was the dramatic incident in 2010 involving Qantas A380 flight QF 32 shortly after takeoff from Singapore Changi when one of its Rolls-Royce Trent 900 engines exploded, the result of a fault in a high-pressure pipeline.

“When you do testing, although it is quite extensive, it’s still not the same as time in actual service. With QF32 it happened to Qantas because it was doing longer average flight duration than any of the other carriers, and that’s why Qantas stopped their operations with the A380 across the Pacific,” Bartsch says.

“There’s a lot of different permutations you’ve got to look at. It wouldn’t be possible during the testing phase to know that there was a product deficiency in terms of the high-pressure pipeline. It comes down to the fact that it takes time … it wasn’t going to happen during the testing. It was only going to happen during the time in service.”

Clearly, the same conclusion can be applied to the problems that dogged Rolls’ Trent 1000 engines last year and which forced carriers such as Air New Zealand to ground B787 Dreamliners (and lease replacement aircraft). The issue was one of reliability with the compressor in the Trent 1000 package C engines not lasting as long as expected, requiring additional inspections and engine replacements.

There were also serious issues for Airbus last year among the Pratt & Whitney Geared Turbofan (GTF) engines powering its popular A320neo, resulting in inflight shutdowns and groundings by operators. While P&W pointed out all three GTF variants were proving their worth to customers, driving significant fuel savings of more than 40 million gallons since entry into service in 2016, it conceded that, with the newest technology and architecture introduced in jet propulsion, it had to work through some “entry into service issues” and focus on supporting customers.

For Rolls-Royce, QF32 and the Trent 1000 problems were a huge wake-up call and a lesson learned that apparently is being put into practice today. In February, the British company announced it had withdrawn from the competition to power Boeing’s proposed NMA (New Midsize Airplane), a program yet to be officially launched. It cited concerns about the proposed timetable, originally set for launch by the end of this year and a 2025 entry into service. Rolls has concluded that it could not meet those challenges in time with its proposed new UltraFan engine. “While we believe the platform complements Boeing’s existing product range, we are unable to commit to the proposed timetable to ensure we have a sufficiently mature product which supports Boeing’s ambition for the aircraft and satisfies our own internal requirements for technical maturity at entry into service,” it said in a statement.

“This is the right decision for Rolls-Royce and the best approach for Boeing,” added Rolls civil aerospace president Chris Cholerton. “Delivering on our promises to customers is vital to us, and we do not want to promise to support Boeing’s new platform if we do not have every confidence that we can deliver to their schedule.”

He said the company remained committed to the UltraFan design and that it would continue to “de-risk” the architecture for future applications.

MAX lockdown

The latest MAX incidents are particularly galling given that the aviation industry has just emerged from two of its safest years on record. Despite rising numbers of aircraft operating in the world’s skies, and passenger numbers increasing at an unprecedented rate, safety statistics show that flying is safer than ever.

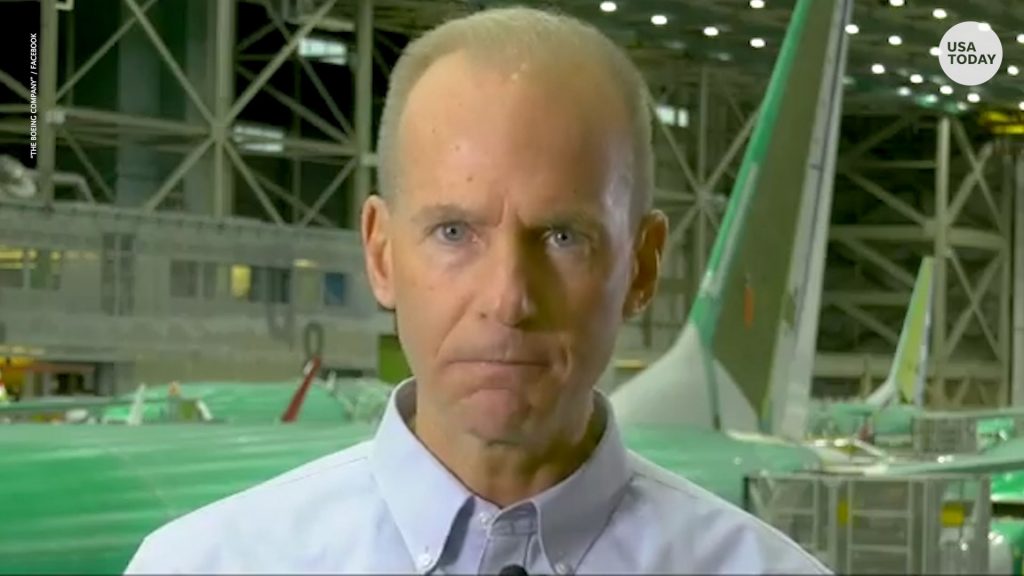

Even in the case of the MAX, and before Boeing succumbed to pressure to agree with the aircraft grounding, chief executive Dennis Muilenburg had sought to assure the public of the safety of the jet: “Since its certification and entry into service, the MAX family has completed hundreds of thousands of flights safely. We are confident in the safety of the 737 MAX,” he told the company’s employees in an internal message.

A day later, as the MAX groundings spread globally and the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) bowed to the US President’s unilateral decision that America needed, belatedly, to do the same, Boeing issued a statement saying it supported that decision even though it “continues to have full confidence in the safety of the 737 MAX”. The company also said it had itself recommended the suspension of the MAX fleet after consultations with the FAA and the National Transportation Safety Board. “We are supporting this proactive step out of an abundance of caution,” Boeing said.

A day later, as the MAX groundings spread globally and the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) bowed to the US President’s unilateral decision that America needed, belatedly, to do the same, Boeing issued a statement saying it supported that decision even though it “continues to have full confidence in the safety of the 737 MAX”. The company also said it had itself recommended the suspension of the MAX fleet after consultations with the FAA and the National Transportation Safety Board. “We are supporting this proactive step out of an abundance of caution,” Boeing said.

As the Ethiopian jet’s black boxes arrived in Paris and the investigation continued, Muilenburg issued another statement reiterating Boeing continued to support the investigation and was working with the authorities to evaluate new information as it became available. “Safety is our highest priority as we design, build and support our airplanes. As part of our standard practice following any accident, we examine our aircraft design and operation and, when appropriate, institute product updates to further improve safety.

“While investigators continue to work to establish definitive conclusions, Boeing is finalising its development of a previously-announced software update and pilot training revision that will address the MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System) flight control law’s behavior in response to erroneous sensor inputs. We also continue to provide technical assistance at the request of and under the direction of the National Transportation Safety Board, the US Accredited Representative working with Ethiopian investigators. In accordance with international protocol, all inquiries about the ongoing accident investigation must be directed to the investigating authorities.”

The MCAS is an anti-stall system which is supposed to bring down the nose of the aircraft if it senses it is climbing at a rate and angle that poses the threat of a stall. It is suspected to be at the heart of the issue, apparently reacting to false data and putting the aircraft into a dive when it has actually been in level flight. That suspicion gained strength as the French Bureau of Investigation and Analysis (BEA) successfully extracted the data from the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) of the Ethiopian Airlines B737 MAX 8 and sent the contents to Addis Ababa, where Ethiopian Transport Minister Dagmawit Moges announced in a press conference that “clear similarities were noted between Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 and Lion Air flight 610”.

These similarities were confirmed on April 4 when the preliminary report on the Ethiopian accident was released by the nation’s Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau (AAIB). It found the pilots followed the guidelines issued by Boeing and disconnected the MCAS to no avail. They then restarted the system but it didn’t help.

“The Boeing 737 MAX 8, registered ET-AVJ, possessed a valid certificate of airworthiness at the moment of the crash, pilots had the correct qualifications and licences to fly the aircraft, takeoff procedures were nominal and Ethiopian Airlines pilots followed all the correct procedures, which did not prevent the nose of the plane from going down,” says the report.

It made two safety recommendations: one asking for Boeing to review the flight control system related to the ability to properly control the flight, the second demanding for aviation authorities to properly review the update of the flight control system made by the manufacturer before the Boeing 737 MAX is deemed airworthy again.

“Despite their hard work and full compliance with the emergency procedures, it was very unfortunate that they (the pilots) could not recover the airplane from the persistence of nose-diving,” says Ethiopian Airlines in a statement.

Boeing’s software update for the MCAS will add more layers of protection from erroneous data out of the aircraft’s angle of attack (AOA) sensors and is expected to be submitted to the FAA for review in the coming weeks.

Significantly, after release of the AAIB report, Boeing’s Muilenburg acknowledged that the MCAS was activated in response to erroneous angle of attack information in both the Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air tragedies.

“The history of our industry shows most accidents are caused by a chain of events,” Muilenburg said in a statement. “This again is the case here, and we know we can break one of those chain links in these two accidents.

“As pilots have told us, erroneous activation of the MCAS function can add to what is already a high workload environment. It’s our responsibility to eliminate this risk. We own it and we know how to do it.”

Competitive pressures

The MAX affair raises series questions over aspects of new aircraft certification, among them competitive pressures. Boeing essentially speeded up its efforts to produce the MAX because it was lagging behind Airbus and was in danger of losing a big order to its rival from major customer American Airlines. The competitive pressure to build the jet – which permeated the entire design and development – now threatens the reputation and profits of Boeing. Prosecutors and regulators are investigating whether the effort to design, produce and certify the MAX was rushed, leading Boeing to miss crucial safety risks and to underplay the need for pilot training, which is the second key element.

AvLaw’s Bartsch is no stranger to safety issues. A former head of safety and regulatory compliance of Qantas and a senior manager with the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority, he has more than 30 years’ operational, safety and regulatory experience across all sectors of the aviation industry.

An experienced pilot with in excess of 7,000 flying hours, he has studied the human factors element in terms of the evolution and uptake of new technology both from a regulatory point of view and as an industry player.

“Obviously getting the integration of new technologies and automation right is absolutely imperative,” he says.

“We saw when Airbus first introduced their fly-by-wire technology the difference between the operating philosophy of the Airbus and the inadequacy of the training of the crew. The whole thing with automation is that it has got to be integrated and introduced so that it becomes a team player with the rest of the operating crew. In order to achieve the benefits of technology and automation it’s got to fit in seamlessly with the crew co-ordination.

“Obviously, there are other issues in terms of what they call in the industry ‘infant mortality’: when you introduce new technology, if you are going to have teething problems that’s likely when you are going to have them.”

He also points to commercial priorities – when engine and airframe manufacturers are keen to get their products to market as quickly as possible, the Trent 900 being a case in point.

“Getting the Trent 900 as the first engine approved for the A380 airframe would obviously give them a huge commercial advantage over their competitors, GE, which had actually fallen behind in their schedule in terms for getting that aircraft engine certified,” says Bartsch.

“And so I think the human factors and the commercial element are often tied into it, and we know that the MAX 8 has seen the fastest number of orders of any aircraft from Boeing on record. So getting new technology out (and) getting aircraft out on time is a high priority, but it can’t be at the expense of not getting it right.”

Bartsch points to wide criticism that many pilots are lacking in basic flying skills. The classic example in recent years is the 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447 from Rio de Janeiro to Paris when the pilot didn’t recognise a looming stall and did exactly the opposite of what he was supposed to – pulling back on the controls instead of pushing forward to increase speed.

It is not an isolated case and raises the question why pilots are not being trained in how to cope when the technology stops working.

Bartsch recalls his own training on the B717 in Long beach, California. “They virtually told us … don’t touch the automation; let the automation do everything for you.

“During my training there was virtually no training on manual reversion at all. It shouldn’t really be left to the airline to make that decision. That should be something that the original manufacturers have as part of their advice material. “But the thing is, with this commercial imperative, if it’s easier to do conversion training onto new types, and they can do it in a shorter period of time, then that is a more attractive (cost) proposition.”

He says only time will tell in the case of the MAX accidents whether or not the pilots really did have adequate training in terms of isolating the system and reverting to manual flying.

“That has been part of the speculation, that perhaps the pilots weren’t even trained as to how to take control.”

The issue of pilot intervention to negate automated control issues on the MAX 8 had already been raised in the US by a number of pilots who lodged reports on a NASA database (they are voluntary safety reports and do not publicly reveal the names of pilots) stating that soon after engaging the autopilot the nose tilted down sharply. They recovered quickly after disconnecting the autopilot. In one report, an airline captain said that immediately after putting the plane on autopilot, the co-pilot called out “Descending,” followed by an audio cockpit warning, “Don’t sink, don’t sink!” The captain immediately disconnected the autopilot and resumed climbing. On another flight, the co-pilot said that seconds after engaging the autopilot, the nose pitched downward and the plane began descending at 1,200 to 1,500ft per minute. As in the other flight, the plane’s low-altitude warning system issued an audio warning. The captain disconnected the autopilot and the plane began to climb.

The reaction of regulators to the crashes also caused some consternation. While China quickly grounded all MAX aircraft, quickly followed by most of the rest of the world, the FAA, normally a leader in such things, hesitated. This globally haphazard approach, says Dr. Hassan Shahidi, president and chief executive of Flight Safety Foundation, was most unfortunate.

“We continue to believe, however, that global aviation safety is best served by timely, harmonised decisions based on facts and evidence, not conjecture, politics, or media pressure. Moving forward, we must allow aviation safety professionals – investigators, regulators, engineers, and pilots – to calmly and objectively analyse the data, collaborate, and implement permanent, corrective fixes to ensure a tragedy like this can never happen again.”

Commercial impact

For Boeing, of course, having two of its brand new aircraft crash so early in their operational life came as an unmitigated disaster. The B737 MAX is expected to account for more than 90 per cent of its planned year-end deliveries and the company’s shares slumped 12 per cent in the days after the Ethiopia crash, wiping out nearly $30 billion in value. Analysts suggest the cost of the software fix could be as high as $500 million. There will also certainly be claims for compensation from the families of those who died. A number of airlines were reported to be re-evaluating orders. Then there is the brand damage and the potential to lose valuable single-aisle orders to rival Airbus. The full impact, however, will depend on how long the groundings last.

As Diogenis Papiomytis, Global Program Director – Commercial Aviation, Frost & Sullivan, put it: “The impact is huge. Boeing was late in announcing and marketing the B737 MAX, the newest version of its most popular aircraft program, back in 2011. This gave Airbus a jumpstart of over a year with their A320neo, and it has not looked back since. In 2019 the neo had 5,700 aircraft orders against MAX’s 3,700. The Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines 737 MAX disasters will, undoubtedly, push this gap even wider.

“Longer-term, the role of Boeing in the duopoly of commercial narrowbody aircraft is at stake. With the introduction of the Chinese Comac C919 and the Russian Irkut MC-21 in 2021, airlines will have more choice.

“Another side-effect is that the aviation industry is now seeing the first signs of overcapacity amidst slowing air traffic growth, driven by a slowdown in the global economy and rising fuel prices. Many airlines may take the opportunity and cancel orders for the B737 MAX in light of a possible downturn. Simply put, the business case for new aircraft in 2019 is completely different to 2015 or 2016, when the airlines placed their orders.”

Ultimately, however, there is little doubt that whatever ails the MAX, a fix will be found and, like the B787 Dreamliner, it will become as good an aircraft as its makers say it is and a major element of global airline fleets. At the same time, more care will have to be taken in the introduction of new technology.

“I think it does come down to basics to a large extent” says Bartsch. “There is no doubt that new technology has an incredibly positive impact on increasing safety and reducing the amount of accidents, but at the same time it is imperative that the basic skills required in the situation where the automation is not functioning appropriately, or needs to be switched off for whatever reason … must be taught during the training or conversion phase.

It comes down to “that overarching ability of the pilots to revert to manual control”.