A Tigerair Australia Boeing 737-800 took off with the cabin unpressurised after the flight crew incorrectly configured the aircraft’s air conditioning system prior to takeoff, an investigation has found.

The incident occurred on July 12 2018, when the 737-800 VH-VUB was operating a flight from Sydney to Melbourne.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) final report, published on Monday, said the trainee first officer did not turn on the cabin air conditioning prior to takeoff.

As a result, a cabin air pressure alarm triggered when the aircraft failed to pressurise.

The crew donned oxygen masks, as required, while they corrected the error and returned to a lower altitude before resuming the flight normally.

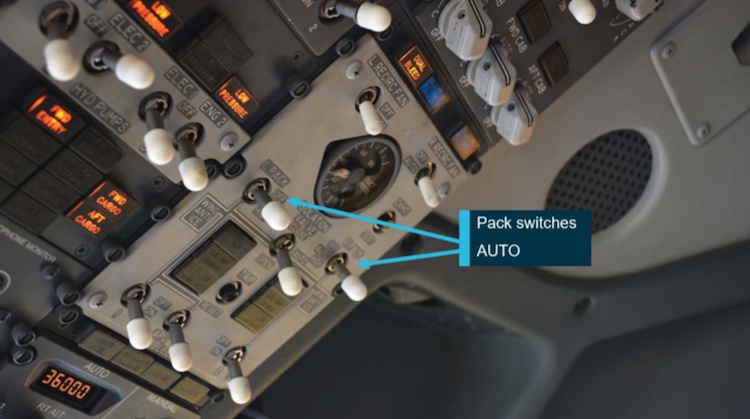

The ATSB said leaving the air conditioning pack switches in the off position highlighted the importance of effective checklist management.

Further, it noted cabin pressurisation was essential to providing a safe and comfortable environment for aircraft occupants flying at high altitude.

“In an unpressurised cabin at high altitude, aircraft occupants are exposed to the possibility of hypoxia (deprivation of oxygen to the body at a tissue level), which can lead to loss of consciousness and possible loss of life,” the ATSB final report said.

ATSB Director Transport Safety Dr Stuart Godley added: “Flight crews are reminded that effective checklist management is essential for verifying that critical procedural items are undertaken and ensuring safe aircraft operation,” .

Tigerair Australia had taken a number of safety actions to ensure the incident is not repeated, the ATSB final report said.

These include notifying its flight crews about adhering strictly to standard operating procedure, summarising its internal investigation into the issue in its quarterly staff publication and reviewing the 737 checklist as well as safety pilot requirements.

The Virgin Australia-owned airline had also introduced a flight operations safety assurance program to identify any potential adverse trends in procedural compliance, line training for its 737 pilots and additional pressurisation event training.

The ATSB final report said the flight crew did not correctly configure air conditioning pack switches and did not identify the error following take-off during pre-flight preparation.

The pilots switched off both air conditioning packs in accordance with the standard operating procedure (SOP) for starting the engines.

However, before taxiing for takeoff the crew did not turn them on to auto, as was required by the SOP. As a consequence the cabin altitude warning presented as the aircraft passed 13,500 ft.

The crew identified that the pack switches were OFF, reset them to AUTO and descended to 10,000 ft, the ATSB final report said. After a short time, cabin pressurisation was under control and the crew continued the flight to Melbourne.

“Cabin pressurisation utilises air bled from the engines, which is distributed throughout the cabin via two air conditioning packs,” the ATSB explained in its final report.

The cabin pressurisation controller modulated the cabin pressure via an outflow valve and was normally set to auto, operating independently of the air conditioning packs attempting to modulate cabin pressure regardless of the pack switch setting.

During normal operation, both packs switches were on auto, but if the packs were off, the outflow valve drive closed to prevent the escape of cabin air. Without bleed air via the air conditioning packs, there was insufficient air to pressurise the aircraft.

The ATSB said the cabin pressurisation controller normally controlled the cabin altitude rate of climb as well as the cabin altitude up to a cabin altitude equivalent of 8,000 ft at the maximum certified aircraft ceiling of 41,000 ft.

The system had both an aural and visual warning for cabin altitude rising above 10,000 ft. Above that altitude, the flight crew was required to use supplementary oxygen. The system also automatically deployed passenger oxygen masks once the cabin altitude rose above 14,000 ft.

“The system has a number of other cautions to alert the crew to a malfunction, but there is no warning or caution to alert the flight crew if air conditioning packs are off,” the ATSB said.

When the horn alert sounded at 13,500 ft, the first officer, who was pilot flying, identified that both air conditioning pack switches were set to off, and immediately switched them to auto before the captain took control of the aircraft.

The crew then completed the remainder of the cabin altitude warning checklist. With cabin pressure under control and operations normal, the flight continued to Melbourne.

The ATSB found that normal procedures and checklists were not completed due to a number of factors, including training, distraction, high workload, low expectancy of error, and supervision lapses.

The investigation noted the first officer, a trainee on the 737, had only recently joined the airline after a lengthy break in flying roles. Also, “significant gaps in the training program may not have allowed the First Officer sufficient time to consolidate the procedures to an intuitive level that was resilient to error”.

Further, the first officer, while having significant experience on other aircraft types such as the 767 and 777, was under supervision from the captain ahead of being checked to the line on the 737.

The ATSB final report said that as the first officer was very experienced, the captain may have relaxed his supervision of the first officer, thus contributing to not identifying the error at the time.

“Whilst the captain reported that he did look at the gauges and switches, he is likely to have had a low level of expectancy of error with regard to the pack switches,” the ATSB final report said.

“His confidence in the first officer’s performance during training and not knowing the first officer to have made that same mistake before is likely to have caused him to not perceive the error, despite looking at the switches.

“This would have been exacerbated by rushing the checklist as he reported.”

Dr Godley said that although the first officer was an experienced pilot, he was still a trainee on the Boeing 737. As such, he required “vigilant supervision” from the training captain.

“This is a crucial defence against error by trainee pilots,” Dr Godley said.

The full report can be read on the ATSB website.