Until recently, the world’s leading aircraft manufacturers Boeing and Airbus were behind on their delivery schedules due to the high demand for their workhorse passenger planes such as the A320neo or 787 Dreamliner.

But now, the demand for new aircraft is drying up as customers don’t order new planes or even cancel their existing orders because of the coronavirus outbreak.

In less than a month, the turbulence has trimmed about US$175 billion in market value from the US aerospace industry, a critical source of American exports. And the future looks just as grim. Passenger revenues could drop as much as US$113 billion this year if the virus spreads extensively, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

“I personally think it will get worse before it gets better,” said Domhnal Slattery, chief executive of Avolon, the third-largest global aircraft leasing company.

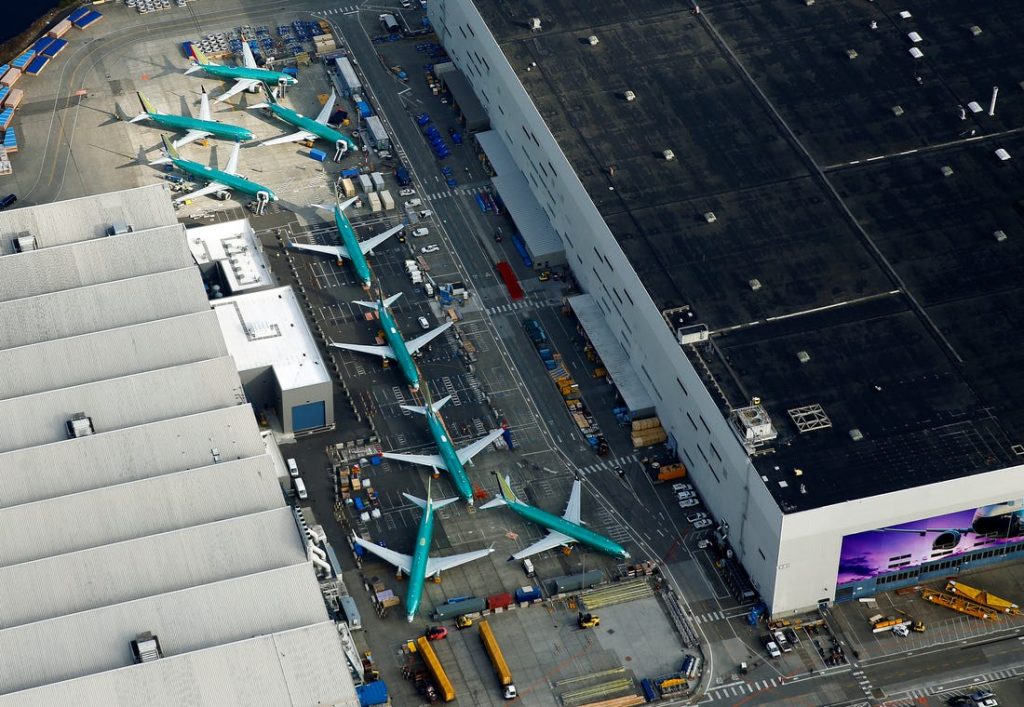

Boeing and Airbus, which were rolling in cash while airlines went on a US$1.15 trillion buying binge stretching back to 2008, are now intently focused on preserving capital and avoiding making “whitetails”. That’s the industry term for the buyer-less aircraft. Even well-heeled carriers such as Delta Air Lines and United Airlines are carefully assessing plans to add new airliners.

Travel restrictions related to the pandemic are preventing airline representatives from China, the biggest international market for new airplanes, from even visiting the Boeing’s delivery centre in Seattle or Airbus’ in France to test-fly and sign ownership papers for new jets.

Other crises

Boeing was already contending with a drop in advance payments from customers of its 737 MAX aircraft, grounded after two crashes. Now that plane is nearing a return to service at a time when few airlines want new aircraft.

The collapse in long-range flying threatens another critical source of cash for Boeing: deliveries of its 787 Dreamliners, which can carry passengers from Sydney to Chicago without refueling. Boeing said it is closely monitoring the market and customer needs. The company has already drawn down $7.5 billion of the $13.8 billion it borrowed in January to help bolster cash until the 737 MAX is back in the market.

“Managing our liquidity and balance sheet are key focus areas,” a Boeing spokesman said, adding that it will “assess all levers to help provide adequate liquidity as we navigate the current challenges”.

During periods of tumult, Toulouse, France-based Airbus sets up what it describes as a watch tower. That involves devoting extra personnel to help distressed customers delay aircraft orders, as well as letting opportunistic buyers jump the line. The company was able to move more than 600 orders around in this way between 2009 and 2011, following the last global economic shock.

The European plane manufacturer is using the same system to manage coronavirus impact, as “commercial, production and finance teams monitor a number of parameters on a daily, weekly and monthly basis”, a spokesman said.

Plunging traffic

Airline traffic is expected to contract this year for only the fourth time since the Great Depression, although the full impact will depend on how long the COVID-19 virus continues to spread, said Ron Epstein, an analyst with Bank of America Corp. Oil prices are also plunging after Saudi Arabia decided to remove pricing curbs, giving airlines less incentive to trade in older, less fuel-efficient models.

“We’re deflating from a very high altitude and that’s concerning. We’ve had one very bad year of traffic, and it’s going to be followed by an even worse year of traffic,” said Richard Aboulafia, an aerospace analyst with Teal Group.

On the sidelines of last week’s ISTAT Americas conference of aircraft financiers, manufacturers and operators in Austin, Texas, executives looked for parallels to the industry slump that lasted two years after the terrorist attacks on 11 Septmeber 2001. During that span, the compound annual growth rate of revenue for Boeing and Airbus and their constellation of suppliers was about minus 11 per cent, by Aboulafia’s calculation.

The correction would be more devastating if airlines hadn’t already cut back because of other problems: the 737 MAX grounding last year, industrial foul-ups that have delayed Airbus’s narrow-body jets and durability issues that have plagued the three major jet engine manufacturers, said consultant Adam Pilarski, former chief economist for McDonnell Douglas before it merged with Boeing.

“If all the airplanes that were ordered that were supposed to be delivered would have come, this bubble would’ve been enormous,” Pilarski said.

“But we started deflating it by having incompetent manufacturers. Luckily, it’s all of them.”

Airline failures?

Still, United president Scott Kirby is among those warning there will be more airline failures, particularly outside of the US. When carriers shut down, they leave behind fleets of used planes – further crimping demand for new models.

“Airlines are desperate to cut capacity, costs and crew, but cannot do it quickly enough. There will soon be airlines going out of business,” said Shukor Yusof, founder of aviation consultant Endau Analytics in Malaysia.

Others are more optimistic, noting that other outbreaks ended in a matter of months, and pent-up demand for travel will return. Over more than a half-century, commercial aviation has weathered so-called “black swan” events where air traffic stalls, only to come back stronger in the end, said John Plueger, CEO of Air Lease, the largest publicly traded US aircraft lessor.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that this, too, shall pass,” he said.

But with China reeling and globalisation waning, the 2020s are likely to be a sobering comedown from the frothy era that followed the 2008 financial crisis.

“We’re into a decade of cooling the jets and sticking to the knitting,” Avolon’s Slattery said.

“I think it’s a decade of growth, but I don’t think it’s the pace we saw over the last decade.”

Article courtesy of airlinerwatch.com